The digital security landscape is continually reshaped by threat actors employing increasingly nuanced and psychologically manipulative attack vectors. A recent, highly targeted campaign, tracked under the designation "PHALT#BLYX" by cybersecurity researchers at Securonix, exemplifies this trend. This operation specifically targets the European hospitality sector, utilizing a sophisticated variant of the ClickFix social engineering methodology. The core mechanism involves masquerading as legitimate system failures—specifically, the infamous Windows Blue Screen of Death (BSOD)—to coerce end-users into manually executing malicious commands that result in the deployment of advanced malware payloads.

To fully appreciate the threat posed by PHALT#BLYX, it is crucial to understand the context of the ClickFix attack paradigm. ClickFix attacks are fundamentally deceptive web experiences designed to create an immediate sense of urgency or technical necessity. Instead of relying on traditional drive-by downloads or exploited vulnerabilities, they place the onus of infection squarely on the victim. The malicious web page presents a fabricated error—be it a security alert, a system update prompt, or, in this case, a system crash simulation—and provides seemingly innocuous instructions, often involving copying and pasting commands into system interfaces like the Windows Run dialog or Command Prompt. The victim, attempting to "fix" the presented issue, effectively becomes the final execution agent for the malware.

The Booking.com Lure and High-Fidelity Phishing

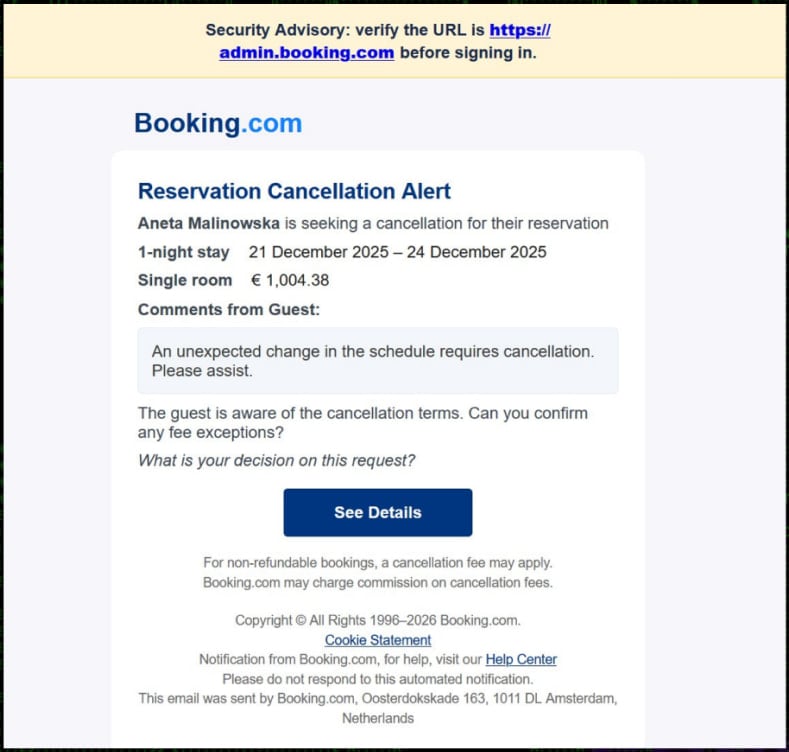

The initiation phase of the PHALT#BLYX campaign demonstrates a keen understanding of operational pressures within the hospitality industry. Threat actors crafted phishing emails designed to mimic official communications from Booking.com, a critical platform for hotels and accommodation providers across Europe. These emails typically alleged a significant reservation cancellation and a corresponding large refund processing failure. This combination of a familiar brand and the high-stakes urgency surrounding financial transactions creates an environment ripe for impulsive decision-making among staff managing reservations and accounts.

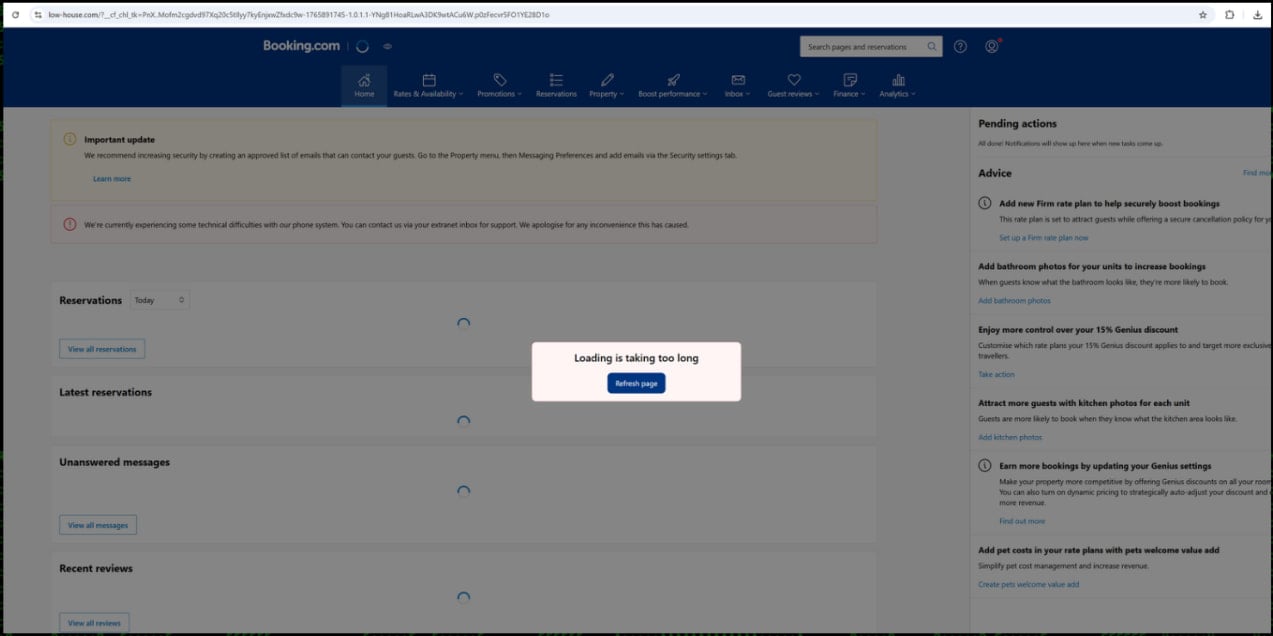

Upon clicking the embedded link, the victim is directed to a fraudulent domain, specifically ‘low-house[.]com,’ which has been engineered into a "high-fidelity clone" of the authentic Booking.com interface. Analysts note the meticulous detail in this replication: correct color schemes, logo placement, and font styling render the page virtually indistinguishable from the legitimate service for an employee under duress or lacking deep technical scrutiny. This level of visual authenticity is a cornerstone of modern, successful phishing operations, moving far beyond poorly translated or obviously flawed imitation sites.

Once on the clone site, the initial deception continues. The JavaScript loaded on the page generates a spurious "Loading is taking too long" error message. This message is a deliberate precursor, guiding the user toward the next action: clicking a ‘refresh’ button, ostensibly to resolve the loading issue.

The Deceptive Transition to System Compromise

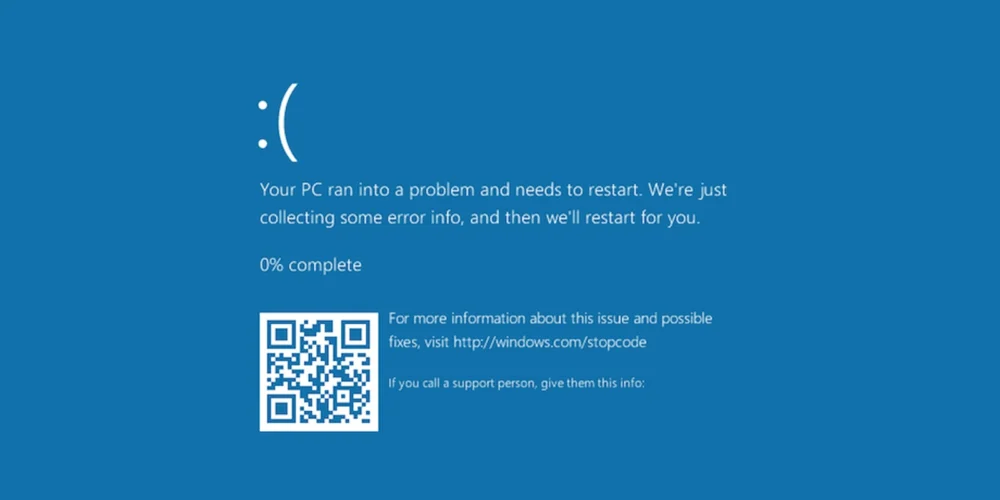

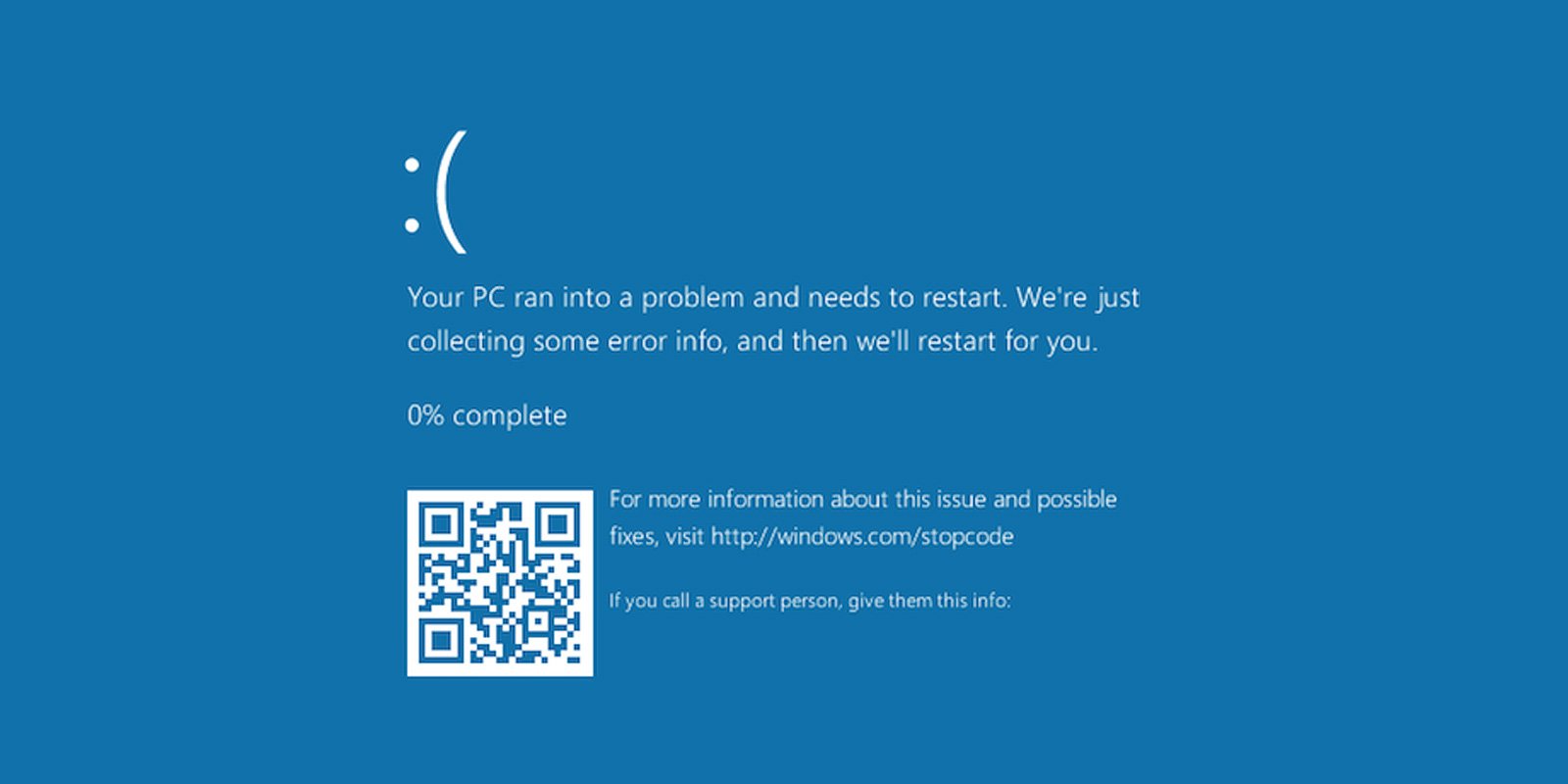

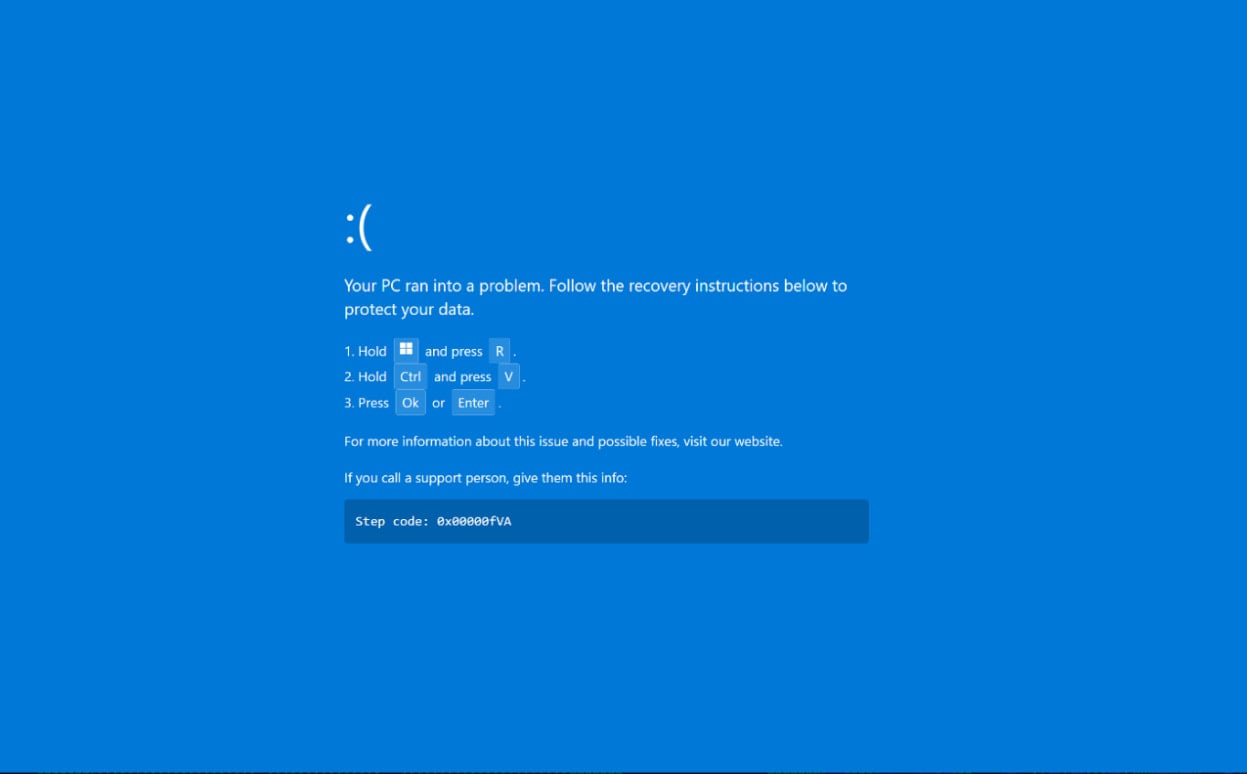

This ‘refresh’ action is the pivot point. Instead of reloading the webpage, the malicious script forces the browser into full-screen mode and overlays the screen with a meticulously rendered simulation of a Windows BSOD. This is where the ClickFix methodology takes center stage, exploiting user familiarity with system crashes.

A genuine Windows BSOD is a critical failure indicator, displaying a stop code and often recommending a system restart. It does not provide step-by-step interactive instructions for recovery. The malicious screen, however, explicitly instructs the user to open the Windows Run dialog (Win+R) and then use CTRL+V to paste a pre-copied command into the input field, followed by pressing Enter or clicking ‘OK.’

This instruction set is highly effective against users who are either less technically proficient or, crucially, those operating under significant time constraints—a common state in front-line hospitality roles dealing with perceived booking errors or financial discrepancies. The cognitive load associated with troubleshooting a supposed system crash, combined with the visual authority of the BSOD graphic, overrides caution.

Technical Execution: From Clipboard to Persistence

The pasted command is typically a complex PowerShell script. When executed via the Run dialog, it initiates a multi-stage infection process designed for stealth and resilience.

- Decoy and Download: The command first opens a seemingly benign decoy—in this case, a window displaying another fake Booking.com administrative page—to keep the user visually occupied. Simultaneously, in the background, the script retrieves a malicious .NET project file (referenced as

v.proj). - Living Off the Land (LotL): A critical technique employed here is the utilization of legitimate, trusted Windows binaries for malicious compilation. The script leverages

MSBuild.exe, the legitimate Microsoft Build Engine, to compile the downloaded .NET project. This technique helps evade simple signature-based antivirus detection, as the execution chain appears to involve a trusted system tool. - Privilege Escalation and Evasion: Once compiled, the resulting payload is executed. It immediately seeks to disable security measures by adding exclusions to Windows Defender definitions. Furthermore, it triggers User Account Control (UAC) prompts, often tricking the user (who has already demonstrated a willingness to execute commands) into granting administrative privileges necessary for deep system modification.

- Loader Deployment and Persistence: The primary infection module is then downloaded using the Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS). BITS is a legitimate Windows mechanism often used for updates, making its network traffic less scrutinized than direct file downloads. To ensure persistence across reboots, the malware drops a

.urlfile into the Windows Startup folder, guaranteeing execution upon the next system login.

Payload Analysis: DCRAT and In-Memory Execution

The ultimate delivered payload, identified as staxs.exe, is identified as DCRAT (DarkCrystal RAT), a sophisticated Remote Access Trojan. DCRAT is a well-known tool favored by various threat groups due to its robust feature set and modularity.

The infection process culminates in a highly evasive maneuver: process hollowing. The DCRAT payload is injected into the memory space of a legitimate, running process, specifically aspnet_compiler.exe. By executing directly in memory within the context of a trusted process, the malware significantly complicates forensic analysis and traditional endpoint detection capabilities that rely on scanning static files on disk.

Upon establishing its initial C2 (Command and Control) connection, the malware transmits a comprehensive system fingerprint—details about the operating system, installed software, and network configuration—allowing the attackers to profile the target environment for tailored exploitation.

The capabilities provided by DCRAT are extensive, including:

- Full remote desktop functionality for visual control.

- Keylogging capabilities to harvest credentials and sensitive communications.

- A reverse shell for interactive command-line access.

- The ability to execute secondary, in-memory payloads without writing them to disk.

In the specific observations documented by Securonix, the threat actors deployed a cryptocurrency miner post-infection. While this suggests a focus on immediate monetization, the underlying DCRAT access grants them far greater potential, including data exfiltration, lateral movement across the hospitality network, and deploying ransomware or other destructive tools.

Industry Implications for the Hospitality Sector

The targeting of the European hospitality sector via this method highlights a significant vulnerability rooted in operational workflow. Hotels, resorts, and related services operate on tight margins, rely heavily on third-party booking platforms, and often have high staff turnover, leading to inconsistent security awareness training.

- Workflow Interruption as a Weapon: The success of PHALT#BLYX hinges on weaponizing workflow interruptions. A "failed refund" or "booking error" is a high-priority event for hotel staff. Security protocols must evolve to recognize that urgent, brand-specific alerts requiring immediate manual input are prime candidates for social engineering.

- Supply Chain Risk Amplification: While the attack impersonates Booking.com, the compromise affects the individual hotel. This underscores the risk inherent in relying on external digital platforms; any breach in the perceived integrity of these platforms can instantly translate into operational risk for the end-user organization.

- The Cost of Legacy Systems and Training Gaps: The reliance on Windows OS features like the Run dialog (a legacy component) for recovery steps suggests that many organizations in this sector may be running older configurations or have insufficient training programs addressing modern, multi-stage browser-based social engineering techniques.

Expert Analysis and Future Threat Trajectories

The PHALT#BLYX campaign is a masterclass in blending established social engineering tactics with advanced technical execution. The use of MSBuild.exe for compilation and process hollowing for payload execution demonstrates an adversary leveraging "Living Off the Land" binaries (LOLBins) to blend malicious activity into normal system operations. This shift away from traditional, easily detectable malware executables toward in-memory execution via trusted processes represents a maturing threat landscape.

Furthermore, the psychological manipulation is tiered:

- Brand Trust: Using a globally recognized brand (Booking.com).

- Urgency/Financial Stakes: Falsifying a critical financial notification.

- System Authority: Leveraging the intimidating visual cue of the BSOD.

- User Action: Requiring the user to perform the final, compromising action.

This layered approach significantly increases the probability of success compared to simple email attachments.

Looking forward, we can anticipate several trends building upon this observed methodology:

Hyper-Personalization of Deception: Attackers will likely increase the fidelity of their phishing attempts by scraping publicly available data (e.g., recent property acquisitions, known local booking issues) to make the initial email context even more believable.

Broader Target Selection: While currently focused on European hospitality, the underlying BSOD ClickFix technique is platform-agnostic in principle. Threat actors could easily pivot to targeting financial services, healthcare administration, or logistics firms by swapping the initial lure (e.g., fake bank transfer error, patient record lock-out) while retaining the BSOD execution mechanism.

Defense in Depth Evolution: Traditional endpoint security struggling against in-memory threats necessitates a greater focus on behavioral analysis. Security solutions must prioritize monitoring abnormal sequences of legitimate process execution, such as powershell.exe invoking MSBuild.exe in conjunction with fileless downloads or unusual network connections originating from system processes. Furthermore, robust User Awareness Training (UAT) must now specifically address the simulation of operating system failures as an infection vector, emphasizing that recovery instructions are never delivered via browser overlays. Organizations must reinforce the principle that any prompt requiring manual command execution from an unexpected source warrants immediate escalation through established internal security channels, regardless of the urgency conveyed by the message. The resilience of the network now hinges on the skepticism of the end-user interacting with seemingly critical, yet fabricated, system alerts.