The modern reliance on digital navigation systems for vehicular travel has reached a point where many drivers treat auditory cues as gospel. For users lacking integrated dashboard displays, or those who must keep their devices secured or out of sight due to environmental concerns, the spoken directions provided by applications like Google Maps become the sole lifeline to a destination. However, recent experiences highlight significant fissures in the reliability of this auditory layer, suggesting that while the underlying map data is vast, the execution of guidance—particularly concerning linguistic nuance and dynamic route adherence—is fundamentally flawed, breeding user distrust.

The Linguistic Barrier: When Voices Fail Place Names

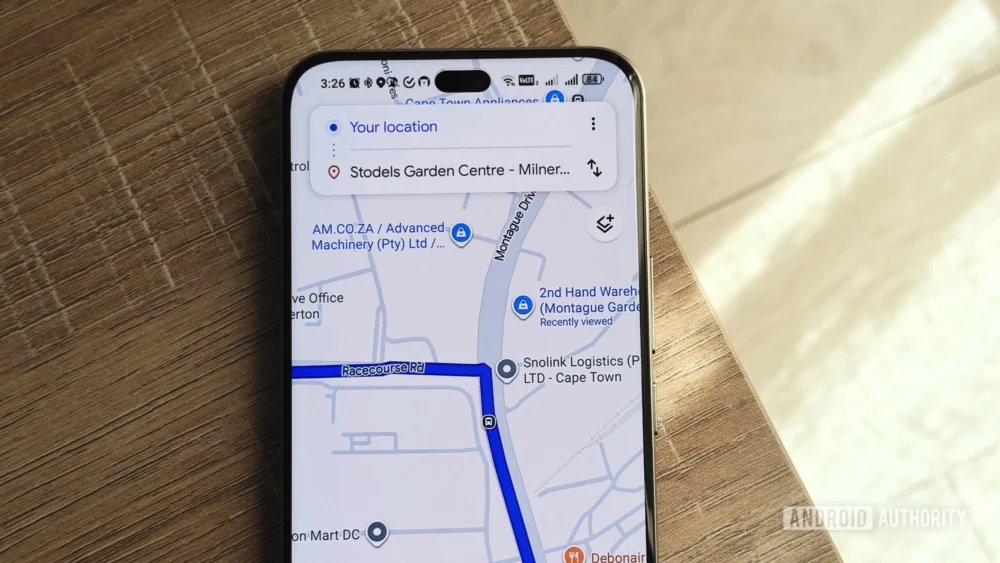

The architecture of global mapping services often prioritizes a single, user-selected primary language for all spoken instructions. This simplification runs headlong into the complex realities of multilingual geographies. Consider highly diverse regions, such as South Africa, which recognizes twelve official languages. In metropolitan areas like Cape Town, street signage and local landmarks frequently incorporate names from English, Afrikaans, and indigenous languages like isiXhosa.

The system’s inability to fluidly handle these linguistic intersections creates critical points of failure. When a user selects English, the system attempts to render every street name using English phonetics. This is manageable for familiar names, or even for recognizing mispronunciations of established English place names (like the silent consonants in "Worcester" or "Leicester," which, while awkward, are generally discernible by context). The severe issue arises when the system encounters terms rooted in languages where the phonetic rules are radically different.

Take the Afrikaans term "weg," meaning "road." In an English setting, Google Maps may render this phonetically as "wag." However, the true Afrikaans pronunciation involves a "v" sound for the initial ‘w’ and a guttural ‘g’ sound, comparable to the ‘ch’ in Scottish "loch." When the navigation system renders "MR559" as "Mister 559," it anthropomorphizes a simple designation. While this might seem minor, when combined with an unintelligible street name, the cumulative effect is total cognitive dissonance for the driver. The spoken instruction becomes a sequence of unrecognizable sounds rather than a navigational marker. If the driver is relying solely on audio cues—perhaps due to poor visibility, adverse weather, or the necessity of keeping the phone stowed—the instruction ceases to be guidance and becomes noise.

This issue transcends simple regional dialectal differences; it involves fundamental phonetic incompatibility between the text string in the map database and the constraints of the synthesized voice model operating under a single language setting. For the global tech industry, this underscores a significant gap in localization efforts: mapping applications need to evolve beyond simple language selection to incorporate localized phonetic dictionaries capable of rendering place names with contextual accuracy, even when constrained by a user’s chosen output language.

Industry Implications: The Trust Deficit in Turn-by-Turn

The navigation sector, dominated by giants like Google and its primary competitor, Apple, is predicated on implicit user trust. When a driver deviates from a route due to an erroneous audio cue, the financial and temporal costs are immediate. However, the long-term cost is erosion of confidence in the platform itself.

In the context of auditory-only navigation, the instruction "turn left onto [Unpronounceable Name]" requires the driver to visually scan for context clues that the audio system was supposed to provide. This forces the driver to divide attention between the road environment and the phone screen, which negates the primary safety benefit of audio-only use. Furthermore, when general directional cues are vague—such as the frequently cited issue of Maps failing to specify "left" or "right" on ambiguous intersections, defaulting instead to a generic "next turn"—the street name becomes the crucial disambiguation factor. If that name is rendered incomprehensibly, the driver is left guessing, potentially leading to hesitation, illegal maneuvers, or sudden lane changes in high-traffic environments.

The case of alphanumeric highway designations (e.g., "MR559" read as "Mister 559") illustrates a failure in basic data parsing within the Text-to-Speech (TTS) engine. While modern AI models should easily distinguish between an abbreviation and a proper noun, this persistent error suggests that the specific routing data for regional roads is not being tagged with appropriate phonetic metadata, forcing the general TTS engine to default to the most common English word matching the letter sequence. This points to a systemic neglect in the quality assurance pipeline for non-major arterial routes.

The Tyranny of Optimization: Unwanted Route Recalculations

Perhaps a more alarming issue than linguistic confusion is the application’s aggressive, often unsolicited, dynamic route modification. Navigation systems are powerful tools for real-time traffic analysis, capable of shaving minutes off a journey by rerouting users around unexpected congestion. However, the manner in which this optimization is presented—and enforced—is a significant source of frustration and operational risk.

When a user manually selects a route, they are often making a conscious decision that prioritizes factors beyond mere travel time. These factors are deeply personal or situational:

- Safety and Security: A user might deliberately choose a route avoiding known high-crime areas, even if it adds ten minutes.

- Vehicle Suitability: Drivers of large commercial vehicles or those towing trailers often select routes free of sharp inclines, low bridges, or narrow streets, regardless of speed.

- Driver Preference: Routes may be selected for scenic value, familiarity (easier recall), or to avoid high volumes of heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) on long hauls, especially during holiday periods when accident rates spike.

Google Maps frequently overrides these nuanced choices by defaulting to an "opt-out" model for suggesting faster routes. If the system detects a potential time saving—even a marginal one, like five minutes on an hour-long trip—it often announces a route change, requiring the user to actively intervene by pressing "Cancel" before the new path is locked in. For an audio-only user, this intervention is impossible until the auditory cue has already been missed or acknowledged.

Worse still are the silent reroutes. A driver relying solely on audio instructions might proceed confidently until the system issues an instruction contradicting known geography ("Turn right now," when the driver knows the road ahead is a straight continuation). By the time the discrepancy is realized, the driver may already be committed to a lane or past the turn point, leading to a significant detour or the need for risky maneuvers. Anecdotal evidence suggests these silent switches occur with alarming frequency, completely undermining the contract between the user and the application: follow the path I selected.

The inconsistencies in this optimization logic are baffling. In one instance, the system will aggressively push the user onto a detour through an entirely different town to save a trivial amount of time, disregarding a user’s explicit initial selection (such as bypassing construction zones or seeking a specific landmark). In another, immediately following a user’s cancellation of a time-saving reroute, the system may suggest an illegal U-turn or a backtracking maneuver that actively increases the journey time by a few minutes, merely because a slightly faster trajectory opens up momentarily on the original path. This suggests the underlying rerouting algorithm lacks a sophisticated understanding of user intent beyond the immediate minimization of estimated time of arrival (ETA).

Future Trends and The AI Overhaul

The current state of navigational audio—riddled with phonetic errors and unpredictable route behavior—sets a low bar for the integration of advanced Artificial Intelligence, such as Google’s Gemini. The critical question for the industry is whether these powerful new models will be deployed to refine existing core functionality or merely layered on top of legacy code to deliver novel, but potentially superficial, features.

The optimistic view suggests that advanced large language models (LLMs) are perfectly suited to solve the linguistic challenges. A properly trained LLM could analyze the geographical context of a street name (e.g., recognizing that in this specific region, ‘weg’ requires a specific pronunciation) and dynamically adjust the TTS output accordingly, potentially even toggling between micro-dictionaries based on GPS coordinates. Similarly, route adherence could be vastly improved. If a user selects Route A, the AI could be trained to understand that "sticking to Route A" supersedes minor time savings, unless a catastrophic event (like a road closure) occurs.

The pessimistic, and perhaps more realistic, view is that the immediate focus will be on integrating generative AI for conversational search or creating highly detailed visual overlays, potentially increasing the application’s computational load and complexity without addressing the fundamental auditory reliability issues that affect millions of drivers daily. If the foundational instructions are untrustworthy, adding conversational features will only add complexity to an already frustrating experience.

For developers in this space, the key takeaway must be that for driving, reliability and predictability trump marginal efficiency gains. Users need a "Route Lock" feature that guarantees adherence to the chosen path unless a mandatory condition (like blockage) prevents it, with any proposed change requiring an explicit, audible, and actionable opt-in confirmation, not a fleeting opt-out notification. Until these basic interface and linguistic fidelity problems are resolved, even the most advanced AI integration will struggle to overcome the ingrained user skepticism resulting from persistent, real-world navigation failures. The shift towards autonomous driving will only amplify this demand for flawless, trustworthy auditory feedback in moments when visual attention is necessarily diverted.