The quest for perfect machine perception has long been defined by a fundamental compromise between resolution and reliability. In the rapidly evolving landscape of autonomous systems—often categorized under the umbrella of "Physical AI" or the "Autonomy of Things" (AoT)—the ability to "see" the world in three dimensions is the prerequisite for every decision a machine makes. For decades, engineers have relied on a bifurcated approach to sensing: the high-resolution but weather-sensitive precision of LiDAR and the rugged but low-resolution reliability of Radar. However, a long-theorized third path is finally moving from the laboratory to the front lines of industrial and automotive application. By exploiting the "Terahertz Gap"—the elusive slice of the electromagnetic spectrum nestled between optical light and radio waves—a new generation of sensors is promising to deliver the best of both worlds, offering high-definition imaging that remains indifferent to the blinding effects of fog, snow, and torrential rain.

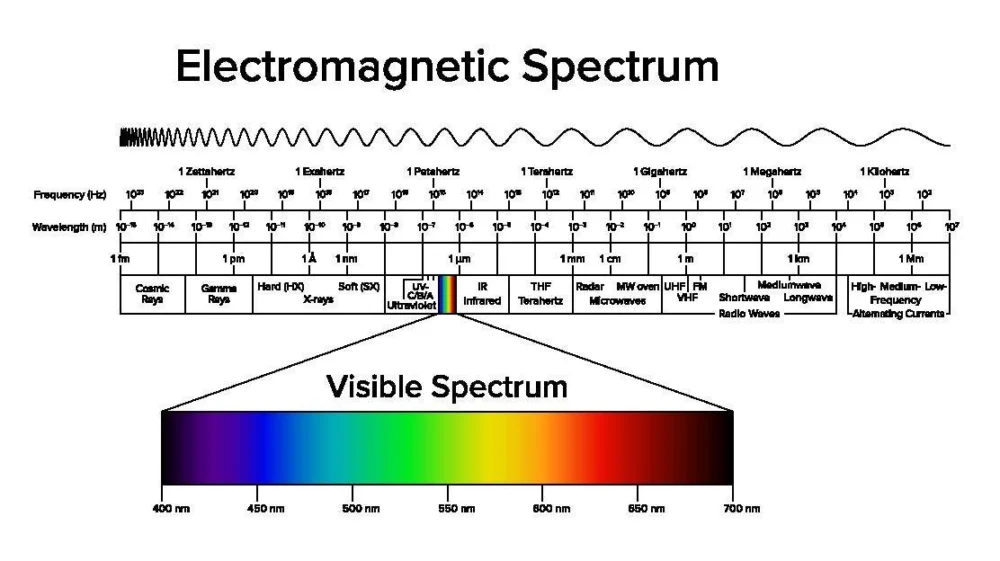

To understand the magnitude of this shift, one must first look at the electromagnetic spectrum as a series of specialized tools, each with inherent physical limitations. Human vision, and by extension the standard cameras used in most mobile devices and vehicles today, operates within a narrow band between 400 nanometers (blue) and 700 nanometers (red). While cameras provide rich semantic data—color, text, and fine detail—they are fundamentally 2D sensors that struggle with depth perception and fail entirely in low-light or obscured environments. To solve the depth problem, the industry turned to LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), which typically operates in the near-infrared or short-wave infrared bands (800 nm to 1550 nm). LiDAR provides stunning 3D point clouds with millimeter-level precision, but because its wavelengths are so small, they are easily scattered by water droplets or snowflakes, rendering the sensor "blind" in adverse weather.

At the other end of the sensing spectrum lies Radar. Operating in the millimeter-wave range (frequencies below 100 GHz and wavelengths between 4 mm and 12 mm), Radar is a mature, battle-tested technology. Its longer wavelengths allow it to pass through atmospheric obscurants with ease, making it the gold standard for all-weather safety. However, this robustness comes at a cost: resolution. Traditional Radar often struggles to distinguish between a stalled car and a metal sign on the side of the road, providing a "blurry" view of the world that requires complex software filtering to be useful for high-level autonomy.

The "Terahertz Gap" refers to the frequency range between 300 GHz and 3 THz, where wavelengths sit between 100 and 1000 micrometers. For years, this region was considered a "no-man’s land" in physics. The waves were too high-frequency to be handled by traditional radio electronics and too low-frequency to be managed by optical components. Furthermore, early Terahertz (THz) imaging systems were notoriously bulky, prohibitively expensive, and consumed massive amounts of power, limiting their use to niche applications like airport security scanners or specialized laboratory spectroscopy.

The recent emergence of Teradar, a Boston-based startup born out of MIT’s "The Engine" incubator, signals that the technological barriers to THz imaging have finally been breached. Founded in 2020 by CEO Matt Carey, radar expert and CTO Gregory Charvat, and Chief Chip Architect Nicholas Saiz, the company has developed a solid-state architecture that brings THz sensing into a form factor and power profile suitable for mass-market automotive and defense applications. With a recent $150 million Series B funding round—backed by heavyweights such as Lockheed Martin’s Capricorn Investment Group and mobility-focused Ibex Investors—the company is positioning THz vision not just as a supplement, but as a potential successor to the current sensor suite.

The technical specifications of this new modality are disruptive. Teradar’s solution offers a native angular resolution of 0.1°, a figure that significantly outperforms conventional imaging radar, which typically hovers around 0.5° to 2°. Through software enhancement, this resolution can be sharpened to 0.05°, bringing it into direct competition with the performance of high-end LiDAR (0.02° to 0.05°). Crucially, this resolution is maintained at ranges of up to 300 meters, even in conditions where LiDAR would be incapacitated. For an autonomous vehicle traveling at highway speeds, this 300-meter window is the difference between a safe stop and a catastrophic collision, particularly in the "Level 3" and "Level 4" autonomy tiers where the human driver is either disengaged or entirely absent.

The backbone of this breakthrough is the Modular Terahertz Engine (MTE). Unlike traditional sensors that are sold as "one-size-fits-all" units, the MTE is a customizable, chip-scale architecture. It utilizes proprietary transmit (Tx), receive (Rx), and "Teracore" processing chips that can be scaled according to the specific needs of the platform. This modularity addresses a major pain point for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). A massive 18-wheeler semi-truck, for instance, requires a much longer sensing horizon than a compact urban delivery robot due to its vastly different braking distances. By simply adding more Tx chips to the modular board, engineers can extend the sensor’s range and field of view without redesigning the entire system architecture.

This scalability extends to the physical integration of the sensor. One of the aesthetic and aerodynamic drawbacks of LiDAR has been its need for a "clear view," often resulting in bulky roof-mounted pods or exposed glass apertures that are prone to dirt and damage. Because THz waves can penetrate many common polymers, Teradar’s sensors can be mounted behind a vehicle’s fascia—the plastic bumper or grill—much like traditional Radar. This protects the hardware from the elements and maintains the vehicle’s design lines, a critical factor for consumer automotive adoption.

The implications of THz vision extend far beyond the highway. In the defense sector, the interest from entities like Lockheed Martin and the former leadership of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) highlights the technology’s strategic value. Terahertz waves offer unique advantages for covert operations and threat detection. Because they operate in a less-crowded part of the spectrum, they are naturally more resilient to the electronic jamming techniques that plague traditional Radar. Furthermore, THz imaging is capable of "spectral fingerprinting." THz waves stimulate specific vibrational modes in organic and inorganic materials, allowing the sensor to identify the chemical composition of an object. In a security context, this means a sensor could theoretically distinguish between a harmless plastic toy and a dangerous explosive, or identify a drone’s carbon-fiber frame against a cluttered background of birds or debris.

In healthcare and manufacturing, this same chemical-sensing capability opens doors to non-invasive diagnostics and real-time quality control. Imagine a manufacturing line where a THz sensor identifies microscopic defects in a polymer seal or detects water vapor intrusion in pharmaceutical packaging—all at the speed of light and without physical contact. In healthcare, the ability of THz waves to interact with water molecules makes them highly sensitive to changes in tissue hydration, offering potential for early-stage skin cancer detection or burn severity assessment without the ionizing radiation of X-rays.

Despite the optimism, the road to mass-market dominance is not without challenges. The automotive industry is notoriously conservative, with long development cycles and a primary focus on cost reduction. Teradar’s current timeline—with "A-sample" R&D sensors for trials in 2025 and mass production targeted for 2028—reflects the rigorous validation process required for safety-critical hardware. The company currently counts eight leading Tier 1 suppliers and OEMs as early partners, suggesting that the industry is taking the "Terahertz Gap" seriously. However, the ultimate success of the technology will depend on whether it can be produced at a price point that allows it to displace, rather than just join, the existing LiDAR-Radar-Camera triad.

There is also the question of sensor fusion. The modern consensus in autonomous driving is that no single sensor is perfect. The industry has moved toward a "fusion" model, where AI-driven software stacks weigh the inputs from various sensors to create a unified world model. If THz vision can truly deliver LiDAR-like resolution with Radar-like weather immunity, it threatens to collapse the need for multiple redundant systems. If one sensor can do the work of two, the savings in compute power, weight, and wiring complexity would be astronomical.

As we look toward the end of the decade, the arrival of Terahertz imaging represents more than just an incremental improvement in hardware; it is a fundamental expansion of the machine-visible world. By mastering the frequencies that were once considered unreachable, engineers are giving Physical AI the "eyes" it needs to operate in the messy, unpredictable reality of the physical world. Whether it is a self-driving truck navigating a midnight blizzard in the Midwest or a defense system identifying a silent threat in a contested airspace, the exploitation of the Terahertz Gap is set to become the new standard for reliability in autonomy. The era of compromising between resolution and resilience is drawing to a close, and the view from the other side of the gap is clearer than ever.