In 2020, Jonathan Benassaya, a seasoned technology entrepreneur who previously co-founded the music streaming giant Deezer, walked into a dermatologist’s office for what he assumed would be a routine, albeit long-delayed, skin examination. The appointment had taken months to secure, reflecting a chronic shortage of specialists in the American healthcare system. When the encounter finally occurred, it was remarkably brief; the physician performed a visual inspection that lasted less than 120 seconds, declared Benassaya healthy, and suggested a follow-up in a year’s time.

The trajectory of Benassaya’s life changed not during the examination, but at the checkout counter. As he was settling his bill, the physician happened to pass by and realized she had neglected to check the area obscured by his surgical mask—a ubiquitous accessory during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Beneath the fabric, on the bridge of his nose, sat a dark lesion. A subsequent biopsy confirmed it was melanoma. Reflecting on the incident, Benassaya is blunt about the stakes: "But for a stroke of luck, I would be dead by now."

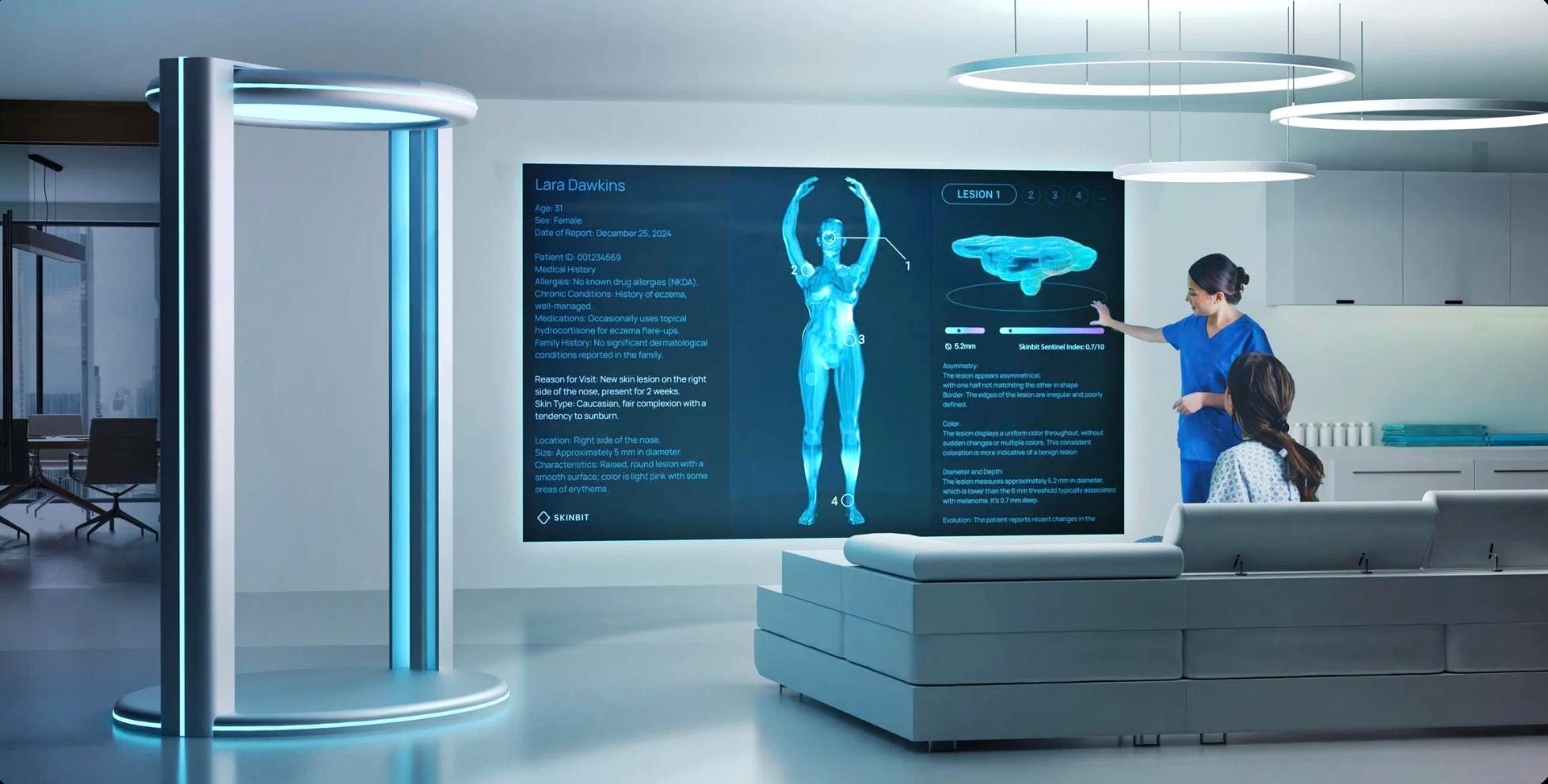

This near-fatal oversight served as the genesis for SkinBit, an artificial intelligence-driven total body scanning system designed to identify skin malignancies years before they progress to a life-threatening stage. Benassaya’s journey from a frustrated patient to a medical tech innovator is not an isolated incident. Instead, it represents the vanguard of a burgeoning movement: the "Patient-Innovator." This cohort consists of technically sophisticated individuals who, after experiencing systemic failures within the traditional medical model, are leveraging advanced AI to build the diagnostic and therapeutic tools their own doctors could not provide.

The Systemic Gap in Traditional Diagnostics

To understand why patients are taking up the mantle of innovation, one must look at the structural vulnerabilities of modern medicine. In the United States, there are approximately 12,000 dermatologists tasked with screening a population of over 330 million. Skin cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in the world, affecting one in five Americans in their lifetime. Yet, the primary method of detection remains largely unchanged since the 1970s: a physician’s naked eye and a dermatoscope.

Benassaya noted the absurdity of this technological stagnation. "We live in a world of high-resolution MRIs, robotic surgery, and AI-driven drug discovery," he observed. "Yet skin cancer… is still detected primarily through visual inspection methods." This reliance on human perception creates a bottleneck. When a specialist is rushed, fatigued, or overwhelmed by a high volume of patients, subtle indicators of early-stage cancer are easily missed.

SkinBit addresses this by replacing the subjective human eye with a digital "twin." The system utilizes an elliptical ring of 16 high-resolution cameras to capture a 360-degree map of the patient’s body in under a minute. Using sophisticated computer vision algorithms, the system creates a 3D model with such high fidelity that it can visualize individual blood vessels and skin textures invisible to the human eye. By training these algorithms on over 50,000 clinical data points, SkinBit can classify lesions and assign risk scores with a claimed accuracy exceeding 90 percent.

The goal is not to replace the dermatologist, but to provide a triage infrastructure that currently doesn’t exist. Benassaya envisions these scanners in pharmacies, gyms, and general practitioner offices, catching cases that would otherwise wait months for a specialist’s brief, potentially flawed glance.

Precision Advocacy: The Case of CureWise

While Benassaya focused on the "missing" diagnosis, Steve Brown focused on the "missing" treatment. Brown, a veteran of the healthcare technology sector, spent a grueling year navigating a series of misdiagnoses before finally being told he had a rare form of blood cancer. The experience revealed a sobering reality: even with a correct diagnosis, the "standard of care"—the baseline treatment protocols followed by most hospitals—is often insufficient for complex or rare cases.

Brown applied his two decades of technical expertise to develop CureWise, an AI-powered platform that acts as a virtual medical advisory board. The system is designed to ingest thousands of pages of unstructured medical records, lab results, and imaging reports to find patterns that human doctors might overlook. When Brown fed his own history into the system, the AI immediately flagged a combination of mild anemia, elevated ferritin, and low immunoglobulins. It suggested specific tests—serum-free light chains and a bone marrow biopsy—that his previous doctors had never mentioned.

What makes CureWise unique is its "Chain of Debate" architecture. Rather than relying on a single Large Language Model (LLM), Brown created a panel of specialized AI agents. One agent adopts the persona of an oncologist, another a hematologist, a third a gastroenterologist, and so on. These agents, powered by different underlying models like OpenAI’s GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude, and Google’s Gemini, "argue" with one another to explore every possible diagnostic pathway. A master model, dubbed "Hippocrates," synthesizes these debates into actionable insights.

This approach allowed Brown to move beyond the standard of care. By using AI to identify off-label drug combinations and prophylactic measures—such as antibody infusions to prevent infection—Brown achieved what he describes as a "miraculous response," bringing his cancer markers back to a normal range. "If you don’t know what to ask for, you’re just going to get standard of care," Brown notes, pointing out that for many cancers, standard treatment response rates can be lower than 30 percent.

A Growing Global Cohort

The stories of Benassaya and Brown are mirrored by a wider global community of patient-engineers. Regina Barzilay, a distinguished computer scientist at MIT, transformed her 2014 breast cancer diagnosis into the development of MIRAI. This deep learning model analyzes mammography images to predict cancer risk up to five years in advance, identifying subtle tissue changes that elude human radiologists.

Similarly, Aaron Babier, while a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, developed AI software to optimize radiation therapy after his stepmother succumbed to a brain tumor. His system reduced the planning time for radiation treatments from several days to just 20 minutes, ensuring that patients could begin life-saving therapy almost immediately. Even the younger generation is contributing; 17-year-old Sachchit Balamurugan developed a high-accuracy AI model for detecting rare cancers after witnessing his grandfather’s struggle with the disease.

What distinguishes these innovators from institutional researchers is their focus on the "user experience" of being a patient. Institutional research often prioritizes broad data sets and generalizable outcomes. Patient-innovators, however, are driven by the specific friction points they encountered: the anxiety of the wait, the opacity of medical jargon, and the frustration of being a "data point" rather than a person.

Industry Implications and the Future of the Doctor-Patient Relationship

The rise of the patient-innovator signals a fundamental shift in the power dynamics of healthcare. For over a century, the medical establishment has operated on a top-down model: knowledge and technology flow from the institution to the patient. We are now entering an era of "participatory medicine," where patients are not just consumers of care, but architects of the tools that provide it.

However, this shift brings significant challenges. Regulatory bodies like the FDA are currently grappling with how to validate "software as a medical device" (SaMD) that evolves through machine learning. There is also the risk of the "digital divide," where only those with high technical literacy and financial resources can build or access these custom AI solutions.

Furthermore, the integration of these tools into clinical practice requires a cultural shift among physicians. Doctors must transition from being the sole "source of truth" to being "navigators" who help patients interpret and validate AI-generated insights. As Brown notes, his AI-driven advocacy only worked because his oncologists were willing to listen and collaborate.

The Road Ahead

As AI models become more accessible and compute costs continue to fall, the barrier to entry for patient-driven innovation will lower. We can expect to see a proliferation of niche AI tools designed for specific rare diseases, chronic conditions, and diagnostic gaps.

The movement led by Benassaya, Brown, Barzilay, and others is a testament to the transformative power of lived experience combined with technical expertise. They have proven that a diagnosis does not have to be a passive sentence; it can be a call to action. By refusing to accept the limitations of the status quo, these patient-architects are not just saving their own lives—they are building a more responsive, precise, and democratic future for global healthcare. The next great breakthrough in medicine may not come from a pharmaceutical laboratory or a university research center, but from a patient sitting at a keyboard, determined to ensure that no one else suffers from the gaps they were forced to bridge themselves.