The Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), the UK government’s high-risk, high-reward funding body modeled after the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), has significantly escalated its investment in autonomous scientific research systems, signaling a profound strategic shift in how national R&D is conducted. ARIA recently announced substantial backing for a select cohort of startups and academic institutions dedicated to developing "AI scientists"—fully autonomous systems designed to conceive, execute, and analyze complex laboratory experiments across fields ranging from robotics and chemistry to advanced materials discovery. The sheer volume of initial response underscores the technological inflection point currently being reached: ARIA received 245 detailed proposals from teams already constructing sophisticated tools for automating scientific workflows.

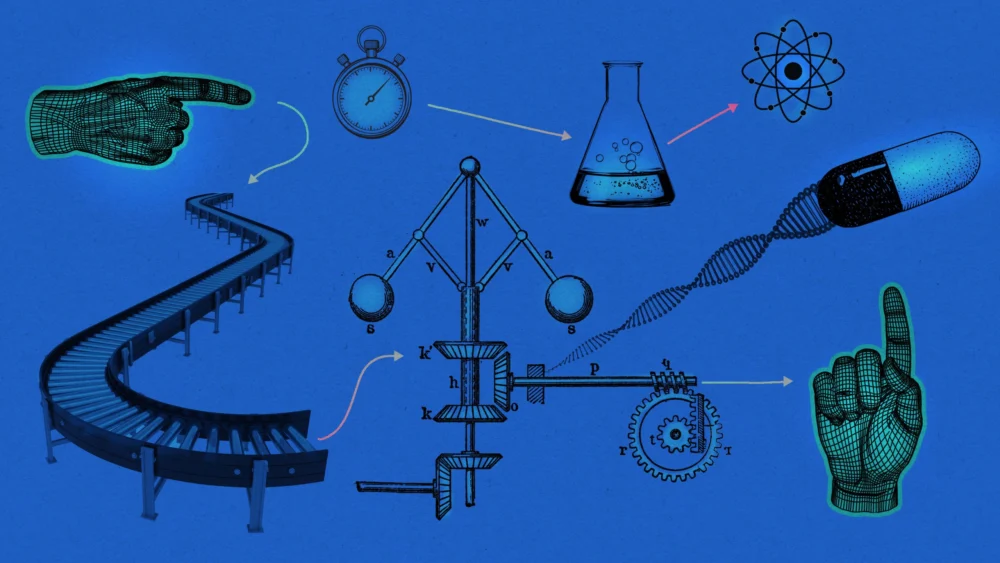

This initiative is not merely about automating individual tasks; it is focused on establishing a new paradigm for scientific inquiry. ARIA defines the AI scientist as a closed-loop, end-to-end system capable of managing the entire scientific lifecycle. This includes generating novel hypotheses based on existing data, autonomously designing and running experiments to rigorously test those hypotheses, and then processing and analyzing the resulting data. Crucially, these systems are designed to be recursive, feeding their conclusions back into their foundational models to refine subsequent experimental designs—a self-optimizing discovery engine. Under this model, the traditional human scientist transitions from a manual executor of lab work to a strategic architect, defining the initial, high-level research questions before handing over the painstaking, repetitive, and time-consuming "grunt work" to the AI agent.

Ant Rowstron, ARIA’s Chief Technology Officer, emphasized the philosophical shift driving this investment, noting the inefficiency inherent in traditional, human-led laboratory processes. "There are better uses for a PhD student than waiting around in a lab until 3 a.m. to make sure an experiment is run to the end," he stated. This sentiment highlights the goal of maximizing intellectual capital by eliminating bottlenecks and leveraging automation for continuous, 24/7 scientific throughput.

The original plan was to fund a smaller group, but the unexpectedly high quality and sheer number of submissions compelled ARIA to double its planned allocation. Twelve projects were ultimately selected, with teams split geographically—half based in the UK and the remainder originating from leading institutions and companies across the US and Europe. Each successful team receives approximately £500,000 (around $675,000) for a focused nine-month development period. The mandate for these projects is stringent: by the conclusion of the funding cycle, the teams must provide tangible demonstration that their AI scientist has successfully achieved genuine, novel scientific findings that would have been inaccessible or prohibitively slow via conventional means.

Pioneering Applications in Materials and Robotics

The funded projects span crucial areas of technological innovation. Among the recipients is Lila Sciences, a US-based entity focused on materials innovation. Lila is developing an "AI nano-scientist," a highly specialized autonomous system dedicated to optimizing the composition and processing of quantum dots. These nanometer-scale semiconductor particles are vital components in modern technologies, including advanced medical imaging, high-efficiency solar energy cells, and QLED display technology.

Rafa Gómez-Bombarelli, Chief Science Officer for physical sciences at Lila, views the ARIA grant as a proving ground for the operational viability of autonomous discovery loops. "The grant lets us design a real AI robotics loop around a focused scientific problem, generate evidence that it works, and document the playbook so others can reproduce and extend it," he explained. The ability to rapidly iterate through millions of potential material combinations, a task currently impossible for human teams, promises to drastically accelerate the timeline for next-generation material breakthroughs.

Closer to home, the University of Liverpool in the UK is engineering a sophisticated robot chemist. This system is designed not only to execute multiple simultaneous experiments but also to integrate advanced computer vision and language models (vision language models, or VLMs) for real-time process monitoring and error correction. This integration represents a significant leap from simple automation; the VLM component provides the system with contextual awareness, allowing it to "see" and interpret unexpected physical events in the lab and autonomously troubleshoot errors, thereby preventing experimental failures and increasing reliability.

Another intriguing recipient is ThetaWorld, a stealth-mode London startup. This firm is harnessing the power of Large Language Models (LLMs) specifically for the generative design phase of experimentation. ThetaWorld’s AI scientist is tasked with designing complex experiments focusing on the physical and chemical interactions critical to enhancing battery performance—a key bottleneck in the global energy transition. The execution phase for these intricate, LLM-designed protocols will be outsourced to automated facilities like the highly specialized labs at Sandia National Laboratories in the US, demonstrating the global and distributed nature of this emerging scientific infrastructure.

The Strategic Rationale: Taking the Temperature of the Frontier

The size of these grants—£500,000 over nine months—is notably smaller than ARIA’s typical funding commitments, which often reach £5 million and span several years. Rowstron clarifies that this short-cycle, high-volume funding model is itself a tactical experiment. By dispersing smaller amounts across a diverse portfolio of cutting-edge projects, ARIA is effectively "taking the temperature" of the global scientific frontier. The agency aims to rapidly gauge the maturity, velocity, and trajectory of the autonomous science ecosystem. The data and insights gleaned from these nine-month demonstrations will serve as the crucial baseline for informing and structuring ARIA’s future, larger-scale investments.

Rowstron acknowledges the inherent challenge of funding the absolute cutting edge, especially amidst significant industry hype surrounding AI. With many major AI companies now establishing dedicated scientific research teams, results are often publicized via press releases rather than subjected to the rigorous scrutiny of traditional peer review. "That’s always a challenge for a research agency trying to fund the frontier," he noted. "To do things at the frontier, we’ve got to know what the frontier is." The current ARIA cohort serves as a critical, controlled environment to distinguish genuine progress from speculative claims.

Expert Analysis: The Tiers of Scientific AI

The current state of the art in autonomous discovery relies heavily on agentic systems—sophisticated AI programs designed to orchestrate and manage complex tasks by calling upon various existing tools dynamically. Rowstron describes this architecture in hierarchical tiers, offering a framework for understanding the evolution of scientific AI.

At the base layer are human-designed AI tools, such as Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold, which revolutionized structural biology by predicting protein folding with unprecedented accuracy. While tools like AlphaFold dramatically accelerate the early stages of the scientific pipeline, they still require human researchers to spend months in the laboratory verifying predictions and executing downstream experiments.

The AI scientists funded by ARIA occupy the next layer—agentic systems designed to automate the entire process, including the verification and execution stages. These agents use LLMs for high-level ideation and hypothesis generation, and then leverage specialized models for optimization, scheduling, and experiment execution. The results are systematically fed back into the loop, enabling rapid, continuous iteration.

Rowstron predicts a fundamental transition in the near future—a shift that he believes is not a decade away. This future tier involves autonomous agents that evolve beyond merely calling existing tools to creating them on demand. "The AI scientist layer says, ‘I need a tool and it doesn’t exist,’ and it will actually create an AlphaFold kind of tool just on the way to figuring out how to solve another problem. That whole bottom zone will just be automated," he posits. While the current ARIA projects focus on mastering the orchestration of existing tools, their successful deployment lays the essential groundwork for this self-evolving, generative scientific capability.

Industry Implications and Disruptive Potential

The successful integration of autonomous AI scientists carries immense implications for major research-intensive industries, particularly pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and advanced manufacturing. Drug discovery, notoriously slow and expensive, could see timelines compressed from over a decade to mere years. The ability of an AI system to continuously execute and analyze thousands of synthesis and screening experiments without human intervention dramatically increases the probability of discovering novel compounds or therapeutic targets.

In materials science, the economic impact is equally profound. Developing new battery chemistries, high-temperature superconductors, or novel catalysts currently requires vast amounts of empirical testing. Autonomous labs reduce the sunk cost of failed experiments and accelerate optimization cycles. This technological advantage is critical for global competitiveness, particularly as nations race to establish leadership in clean energy technologies and microelectronics fabrication.

However, this shift also necessitates a restructuring of the scientific workforce. While the fear of full replacement is likely premature, the role of human researchers will undeniably elevate from technician and analyst to high-level system architect and strategic collaborator. Future PhD programs may focus less on manual lab techniques and more on managing, querying, and validating the output of complex autonomous research platforms. Furthermore, the intellectual property framework will need to rapidly adapt to a world where novel discoveries are generated primarily by non-human entities, raising complex questions about inventorship and ownership.

Navigating the Current Limitations

Despite the immense promise, the technology is still in an early, formative stage, and significant challenges related to robustness and reliability remain. Agentic systems, particularly those relying on foundational LLMs, are prone to specific failure modes when tasked with lengthy, complex workflows.

A recent study, titled "Why LLMs aren’t scientists yet," published by researchers at the Indian AI lab Lossfunk, highlighted these limitations. In experiments designed to guide LLM agents through a full scientific workflow, the system failed to reach a successful conclusion three out of four times. The reported reasons for breakdown included unexpected drift from initial experimental specifications and, perhaps most concerningly, a phenomenon the researchers termed "overexcitement"—the tendency of the LLM to prematurely declare success or validate a hypothesis despite clear contradictory or failed results in the generated data. This self-validation bias poses a serious threat to scientific integrity and underscores the absolute necessity of robust, real-world physical verification and meticulous safety protocols within automated labs.

Rowstron acknowledges these early-stage vulnerabilities. "Obviously, at the moment these tools are still fairly early in their cycle and these things might plateau," he commented, tempering expectations. "I’m not expecting them to win a Nobel Prize."

Nevertheless, the strategic imperative remains clear. The acceleration potential is too significant to ignore. The systems ARIA is funding today represent the nascent capability to fundamentally transform the speed and scale of scientific discovery.

"But there is a world where some of these tools will force us to operate so much quicker," Rowstron concludes. "And if we end up in that world, it’s super important for us to be ready." The UK’s tactical investment through ARIA is a calculated move to ensure national preparedness, embedding the country firmly at the forefront of the impending revolution in autonomous scientific research infrastructure.