The global energy transition, fueled by aggressive decarbonization mandates and the urgent necessity for resilient power infrastructure, has propelled the nuclear energy sector into an undeniable period of revival. This renaissance is characterized not merely by the maintenance of existing fleet capacity, but by a feverish, venture-backed pursuit of novel reactor designs. Investment capital is flowing into nuclear technology startups at levels unseen in decades. The latter weeks of 2025 served as a microcosm of this financial enthusiasm, witnessing nuclear startups collectively secure over $1.1 billion in funding, signaling profound investor conviction that next-generation, smaller nuclear reactors represent the viable path forward for reliable, carbon-free baseload power.

This monumental investment wave is predicated on a fundamental rejection of the conventional nuclear construction paradigm. For decades, the industry standard has been the deployment of massive, bespoke infrastructure—gigawatt-scale reactors requiring years of on-site construction and staggering capital commitments. The experience of the newest U.S. nuclear projects, such as Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia, stands as a stark, multi-billion-dollar warning against this model. These facilities, each designed to generate more than one gigawatt of electricity and containing concrete volumes measured in the tens of thousands of tons, were plagued by delays that stretched the timeline by eight years and exceeded initial budget forecasts by upwards of $20 billion. The sheer complexity, scale, and inherent risk of this approach have made large-scale nuclear construction almost financially untouchable for private enterprise.

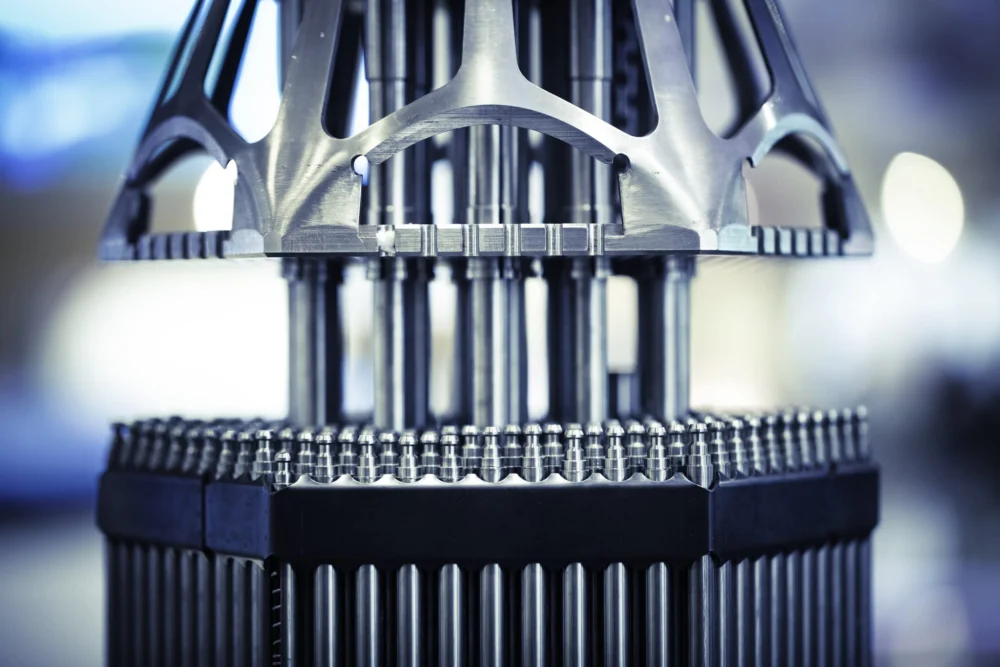

The current generation of nuclear startups, often centered on developing Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) or microreactors, offers a compelling solution to the industry’s historical woes: radical reduction in size and a shift toward factory fabrication. By shrinking the physical size and power output—some designs are rated as low as a single megawatt—these firms aim to modularize construction. The strategy is straightforward: rather than constructing a unique, monolithic structure on site, the core reactor components are manufactured in a controlled factory environment and then shipped for rapid assembly. If greater power output is required, the solution is not to build a larger reactor, but simply to deploy multiple standardized units.

This approach pivots the economic model from economies of scale (building one massive plant) to economies of volume (building many small, identical units). Proponents argue that high-volume, standardized production will unlock significant cost reductions via the "learning curve" effect. As production volume increases, efficiency improves, waste decreases, and manufacturing costs per unit drop predictably. This cost-reduction forecast, known in the industry as achieving the "Nth-of-a-Kind" (NOAK) cost target, is the holy grail for nuclear finance, promising competitive levelized costs of electricity (LCOE) that have historically been unattainable.

While the theoretical benefits of modularity and factory production are sound, translating this vision from concept to commercial reality requires overcoming formidable, non-trivial challenges rooted deep within the industrial supply chain and workforce infrastructure.

Manufacturing advanced nuclear technology is vastly more complex than assembling consumer electronics or even mass-produced automobiles. The materials required are often highly specialized, designed to withstand extreme temperatures, high pressure, and intense radiation fields over decades. This necessity for exotic alloys and high-purity components exposes a critical vulnerability in the domestic industrial base.

Milo Werner, a general partner at DCVC with extensive experience in scaling complex manufacturing operations at companies like Tesla and FitBit, underscores the severity of this supply chain deficit. “I have a number of friends who work in supply chain for nuclear, and they can rattle off like five to ten materials that we just don’t make in the United States,” Werner noted. “We have to buy them overseas. We’ve forgotten how to make them.”

The decline of the U.S. heavy manufacturing sector over the past four decades, driven by widespread offshoring, has resulted in the degradation of critical national industrial capabilities. This is a crucial differentiator for nuclear startups compared to, for example, the electric vehicle sector. When Tesla navigated its infamous "production hell" phase for the Model 3, it did so within a country that still possessed a foundational knowledge base, supply chain infrastructure, and skilled workforce related to high-volume automotive production. Nuclear energy, particularly the advanced designs now being developed, requires competencies—such as the fabrication of specialized reactor pressure vessels, high-temperature heat exchangers, and unique fuel element cladding—that have atrophied or vanished entirely from the domestic market. Re-establishing these complex supply chains is a prerequisite for achieving the promised NOAK cost targets, yet it demands massive, patient capital investment far exceeding the initial startup rounds.

Beyond the challenge of materials and specialized component fabrication, the nuclear renaissance faces a profound human capital crisis. While the sector is currently “awash in capital,” as Werner observes, funding cannot compensate for a deficit in seasoned manufacturing expertise. The prolonged hiatus in large-scale industrial construction in the United States has led to a significant erosion of the industrial "muscle memory" necessary to build and operate complex, large-scale factories, let alone those requiring nuclear-grade precision and quality assurance.

“We haven’t really built any industrial facilities in 40 years in the United States,” Werner explained. This lack of continuous industrial activity has resulted in a severe talent gap spanning the entire manufacturing hierarchy. It’s not simply a shortage of highly specialized nuclear engineers, though that exists; the deficit extends to every level: experienced factory floor supervisors, quality control specialists certified for nuclear components, specialized trades like high-purity pipe fitters and welders, and even C-suite executives and board members who possess the operational experience required to manage the unique risks and regulatory demands of scaling nuclear manufacturing.

The implications of this talent gap are substantial. Scaling a new technology, especially one as highly regulated as nuclear power, requires iterative improvement—a rapid feedback loop between design, manufacturing, and operational testing. If the team responsible for production lacks foundational expertise, the learning curve flattens, quality suffers, and the expected cost reductions fail to materialize. As Werner cautions, the lack of seasoned personnel makes the scaling process akin to trying to "run a marathon the next day" after years of inactivity.

This domestic manufacturing deficit creates significant industry implications, particularly regarding global competition. Nations like Russia, China, and South Korea, which have maintained active, state-backed nuclear construction programs and robust industrial bases, are aggressively pursuing their own SMR designs. They are positioned to potentially leapfrog Western startups in achieving serial production and accessing export markets because they do not face the same structural manufacturing and workforce hurdles. For U.S. startups to remain competitive, they must not only innovate in reactor physics but also pioneer advanced manufacturing techniques, such as additive manufacturing (3D printing) of reactor components, to bypass traditional, slow fabrication bottlenecks.

To mitigate these risks and realize the investment potential, nuclear startups are adopting strategies focused on rapid iteration and localization. Many are wisely building initial, smaller versions of their products and manufacturing infrastructure in close proximity to their core technical teams. This co-location accelerates the cycle of design-manufacture-test improvement, allowing engineers to quickly diagnose and refine production processes, thereby "pulling manufacturing in closer to the United States."

Furthermore, investors are prioritizing designs that fully embrace modularity. Modularity is not just about size; it is an approach to manufacturing that allows companies to start with low-volume production runs early in the development cycle. This yields crucial data on manufacturing yield, supply chain reliability, and process efficiency. Collecting and analyzing this data over time provides tangible evidence of progress on the learning curve, offering crucial reassurance to investors who are betting on future cost parity.

However, even with the most sophisticated manufacturing strategies, the promise of mass production savings will not be immediate. The history of complex technology development shows that achieving transformative cost reductions through serial production is a long-term endeavor. Companies must be prepared for a sustained capital deployment over an extended timeline. Achieving the full benefits of a highly optimized manufacturing process, where cost reductions are steep and reliable, “often takes years, like a decade, to get there,” Werner advises.

The future impact of SMRs hinges on navigating this complex intersection of financial optimism and industrial reality. Successfully establishing a domestic nuclear manufacturing base requires more than just venture capital; it necessitates long-term policy commitments. These include government support for workforce training programs focused on specialized nuclear trades, strategic public-private partnerships to rebuild domestic capacity for critical materials (e.g., advanced ceramics and metallic alloys), and a commitment from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to standardize and expedite the licensing process for factory-built, standardized SMR designs.

If the industry can overcome the deep-seated challenges in supply chain resilience and human capital formation, SMRs are poised to transform the energy landscape. They offer solutions for remote industrial power, replacement of retiring coal plants, and provision of reliable power to remote communities and data centers. The current capital infusion provides the necessary fuel, but the ultimate success of the nuclear renaissance rests not on the brilliance of the physics, but on the disciplined, decade-long effort to master the industrial complexity of mass manufacturing. The bottleneck is no longer in the reactor design, but in the factory floor and the skilled hands required to build it.