The dramatic corporate transformation of Twitter into X served as a potent catalyst, driving millions of users to seek refuge in alternative microblogging environments. While newer, venture-backed contenders like Bluesky and the corporate behemoth Threads quickly entered the fray, it was Mastodon, a platform established quietly in 2016, that offered the most fundamentally distinct vision for the future of social networking. Mastodon’s resilience and subsequent surge in relevance stem not from replicating the centralized model of its competitors, but from championing an open, federated, and non-profit infrastructure—an ethos that stands in direct opposition to the commercial interests dominating Web 2.0.

Defining Decentralization: The Architecture of the Fediverse

Mastodon was engineered by German software developer Eugen Rochko with a core philosophy rooted in public benefit rather than proprietary control. Crucially, the platform operates as a non-profit entity, eliminating the pressure to prioritize shareholder value over user experience or ethical moderation.

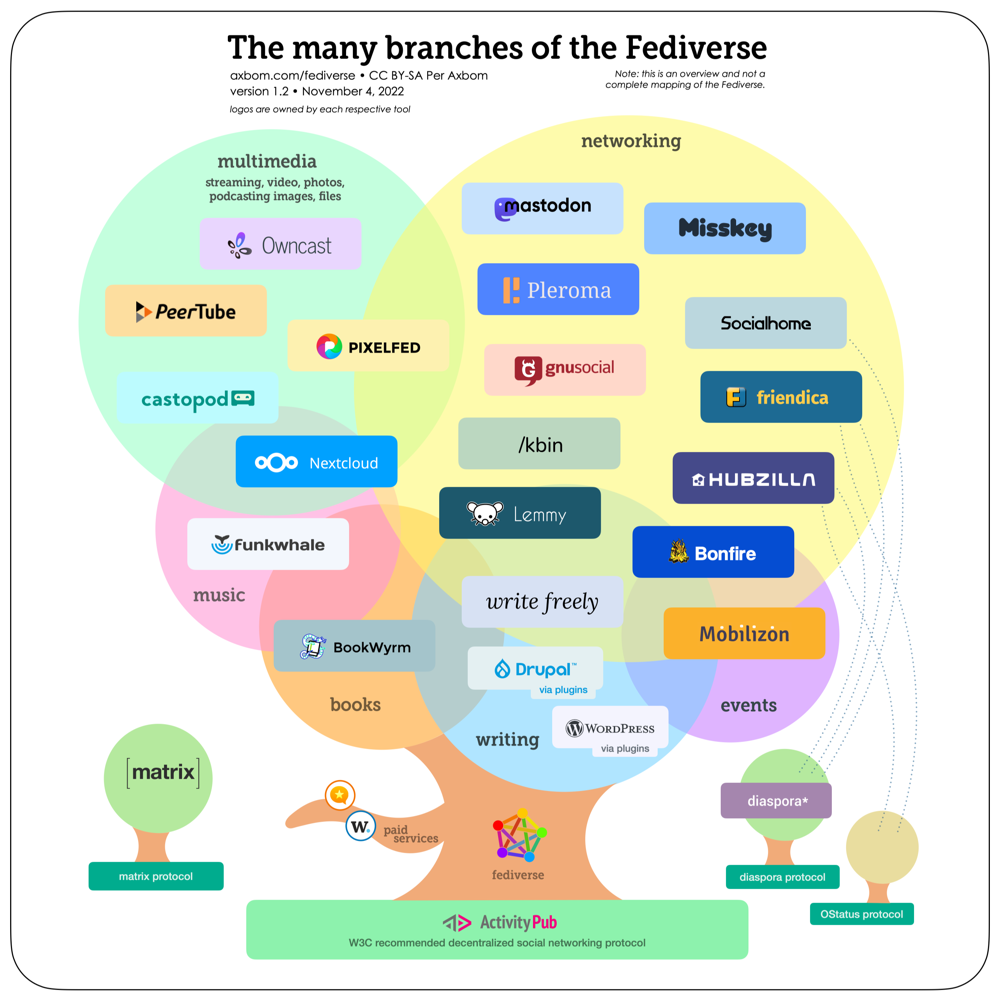

While superficially resembling traditional microblogging sites, Mastodon’s underlying technology is radically different. It is not decentralized in the often-misunderstood, ledger-based sense of blockchain technology; rather, it is federated. This architecture operates much like the global email system, where users on Gmail can seamlessly communicate with users on Outlook or corporate mail servers. Mastodon is the primary, but not the only, application within this interconnected ecosystem known as the Fediverse (Federated Universe).

The technical foundation enabling this federation is the ActivityPub protocol. ActivityPub allows independent servers running compatible software to exchange data, posts, and user interactions. This means a single Mastodon account serves as a passport across various decentralized social networks built on the same standard. Unlike proprietary silos, where a user’s Instagram identity is walled off from their X identity, the Fediverse allows for genuine network portability and interoperability.

Instances, Identity, and Interoperability

The primary unit of organization within Mastodon is the instance, or server. These instances are independent, self-hosted nodes run by individuals, groups, or organizations, each bearing the full responsibility for its own maintenance, community guidelines, and content moderation.

When a new user joins, they select an instance, which then determines their unique network address. For example, a user joining a technology-focused server might have an identity formatted as @[email protected]. This structure clearly indicates both the individual user and their home server. Despite residing on separate servers, users can follow and interact with anyone else across the entire Mastodon network, provided their respective instances have not chosen to block (or "defederate") from one another due to violations of community trust or policy.

This architectural choice has profound implications for user agency. If a user disagrees with the policies or administration of their current instance, they retain the freedom to migrate their account and followers to a new instance, avoiding the vendor lock-in inherent in centralized platforms.

The Philosophical Weight of Open Source

Mastodon is fundamentally an open-source project. This designation is not merely a statement about transparency; it carries legal and developmental weight. The software is released under licenses that permit anyone to download, inspect, modify, and install the platform’s code on their own server, without needing permission from the original development team. Critically, the developers do not own the copyright on the collective software ecosystem.

This open nature ensures accountability. The source code is constantly scrutinized by a global community of developers, which enhances security and prevents the introduction of proprietary "black box" algorithms that often dictate content visibility and advertising on centralized platforms.

The importance of adhering to open-source licensing principles was highlighted by the controversy involving Truth Social. When the platform launched using adapted Mastodon code without proper acknowledgment or adherence to licensing requirements, the Mastodon team enforced the General Public License (GPL), demonstrating that the code’s freedom is protected by enforceable legal mechanisms designed to prevent proprietary hijacking of communal technology.

Understanding the Mastodon User Experience

For new users accustomed to the seamless, monolithic interface of X, the Mastodon experience requires a slight learning curve, primarily centered around understanding the concept of multiple, yet connected, communities.

Timelines and Discoverability

Mastodon offers distinct timeline views, designed to give users granular control over their content stream:

- Home Timeline: Standard view showing posts from all accounts the user follows, regardless of their instance.

- Local Timeline: Displays all public posts made by users specifically on the user’s home instance. This fosters a tight-knit community feel, unique to the server.

- Federated Timeline: An expansive firehose view, showing all public posts from users that anyone on the user’s local instance follows. This serves as the primary gateway for discovering new users and content across the broader Fediverse.

While the term "toots" for posts has largely faded in favor of the more conventional "posts," the platform supports familiar microblogging conventions: replies, boosts (the equivalent of retweets), favorites, bookmarks, and hashtags.

A notable distinction from centralized platforms is Mastodon’s approach to content discovery and safety. By design, user search is restricted primarily to hashtags and metadata (posts the user has written, favorited, or been mentioned in), not the full text of every public post. This intentional limitation is a feature built to mitigate large-scale harassment and "dogpiling," as trolls cannot easily conduct coordinated, word-based searches across the entire network to target individuals.

Moderation and Safety

Because moderation is delegated to individual instance administrators, Mastodon’s safety profile is heterogeneous. A user seeking a highly controlled environment with strict rules against hate speech or misinformation can choose an instance known for its robust and rigorous moderation policies. Conversely, another user might opt for a looser, more permissive server.

This distributed moderation model contrasts sharply with the single, top-down policy enforced by corporate entities like X, where policy shifts are often sudden, opaque, and driven by commercial or political expediency. On Mastodon, if an instance’s moderation fails, users can simply move to a different server, taking their social graph with them. This puts direct pressure on instance admins to maintain a healthy community or risk losing their user base.

The Industry Implications: Competing Protocols and Corporate Federation

The ongoing turmoil in the microblogging space has intensified interest in decentralized social networking, drawing the attention of both idealistic startups and established tech giants.

Mastodon vs. Bluesky

Mastodon’s primary rival in the decentralized sphere is Bluesky, which emerged from a project incubated within Twitter. However, Bluesky made a critical strategic decision: instead of adopting the established ActivityPub protocol, it developed its own networking standard, the AT Protocol (Authenticated Transfer Protocol). Bluesky’s rationale was that existing protocols did not fully meet their goals for enabling global, long-term public conversations at massive scale.

This divergence represents a significant philosophical split in the future of decentralization. Mastodon and the Fediverse prioritize interoperability and community governance through an open, existing standard. Bluesky, by creating a new protocol, aims to build a more flexible, scalable system from the ground up, but risks creating a separate, potentially controlled, decentralized ecosystem. While the AT Protocol is open source, the decision to create a proprietary specification draws skepticism from the open-source community regarding potential long-term control by the founding entity.

The Threads Factor and Protocol Legitimization

The competitive landscape shifted dramatically with the entry of Meta’s Threads. Despite being a highly centralized, corporate platform, Threads made the groundbreaking decision to integrate support for ActivityPub. This move, announced in 2024, instantly injected the potential for hundreds of millions of users into the Fediverse, effectively legitimizing ActivityPub as a viable internet standard for social data exchange.

For Mastodon, this means posts from Threads users can potentially be viewed, replied to, and interacted with by users on ActivityPub-compliant servers, bridging the gap between a colossal corporate audience and the independent, decentralized network. This development presents both an opportunity (massive influx of potential reach) and a governance challenge (how to moderate interactions with a single, massive corporate actor). The successful integration of Threads validates the architectural principles of federation while simultaneously testing the Fediverse’s ability to maintain its independent, non-commercial identity in the face of corporate scale.

Future Trajectories and Scaling Trust

As of mid-2025, Mastodon’s user base remains modest compared to X, with under one million monthly active users and around 10 million registered accounts. This limited scale presents the platform’s greatest challenge: overcoming the network effect. X remains the global "water cooler"—the default source for immediate, high-volume news and cultural discourse. Mastodon, conversely, excels as a network of highly engaged, focused communities.

The future viability of Mastodon and the Fediverse hinges less on reaching the raw scale of X, and more on cementing its role as the preferred digital home for specialized, niche, and professional communities. Whether it’s academics, tabletop gaming enthusiasts, or climate justice activists, the ability to create a custom, self-moderated space with known rules and boundaries is Mastodon’s core competitive advantage.

However, scaling trust remains a crucial hurdle. In a centralized platform, trust is placed solely in the corporation (e.g., Meta or X). In the Fediverse, trust is distributed among hundreds of administrators. For Mastodon to achieve mainstream recognition, it must continually improve the user experience surrounding server selection, ensuring that newcomers can easily find well-governed, reliable instances that align with their values.

Ultimately, Mastodon is not simply a replacement application; it represents an infrastructure movement. Its open-source, federated foundation, powered by ActivityPub, challenges the prevailing model of proprietary control over digital identity and communication. By offering choice, portability, and community self-determination, Mastodon provides a robust, decentralized alternative that is likely to endure, regardless of the fluctuating fortunes of centralized competitors.