In the annals of interactive entertainment, few platforms occupy a space as mythical and ephemeral as the Sega Channel. Launched in the mid-1990s, it was a visionary precursor to the modern era of digital distribution, a service that beamed video games directly into living rooms via cable television lines long before the term "broadband" had entered the public consciousness. For decades, much of the unique content produced for this service was considered "vaporware" in reverse—software that existed, was played by thousands, and then vanished into the ether once the servers were deactivated. However, a monumental breakthrough in video game preservation has recently rewritten this narrative. Through a sophisticated multi-year effort, archivists and historians have successfully recovered 144 previously "undumped" ROMs, effectively salvaging a critical chapter of gaming history that was on the brink of permanent erasure.

This recovery operation, spearheaded by the Video Game History Foundation (VGHF), represents one of the most significant triumphs for digital conservation in recent memory. By unearthing rare game variations, lost prototypes, and exclusive demos, the project has provided a window into an era of radical experimentation. The recovered data includes not just the games themselves, but the internal documentation and technical blueprints that powered this early "Netflix for games." The implications of this find extend far beyond mere nostalgia; they offer a profound look at the industry’s first serious attempt to decouple software from physical media, a shift that defines the contemporary gaming landscape.

The Audacity of the Sega Channel

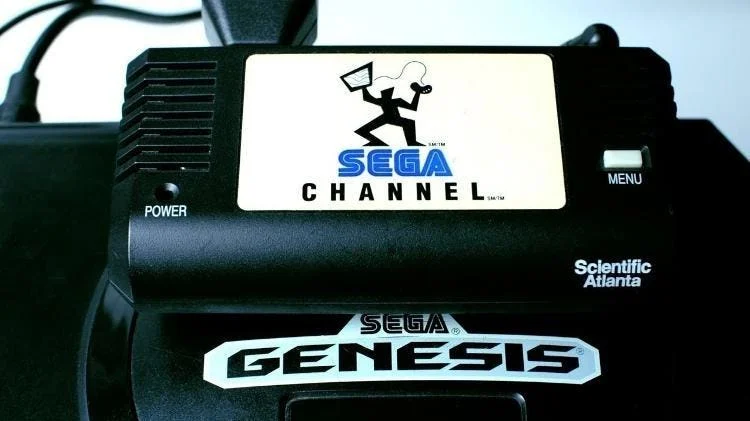

To understand the weight of this recovery, one must first appreciate the sheer technological audacity of the Sega Channel at the time of its inception. When it debuted in the United States in late 1994, the internet was a nascent curiosity for the vast majority of households. Most users were tethered to 14.4k or 28.8k modems, making the digital delivery of a 16-megabit Genesis game an impossibility over standard telephone lines. Sega’s solution was to bypass the phone lines entirely and leverage the high-bandwidth infrastructure of cable television.

In partnership with cable giants TCI and Time Warner, Sega developed a specialized adapter that slotted into the Sega Genesis cartridge port. This device acted as a sophisticated tuner, capable of "listening" to a specific frequency on the cable line where game data was being continuously broadcast in a carousel format. When a subscriber selected a game from the on-screen menu, the adapter would wait for that specific packet of data to cycle through the broadcast, capture it, and load it into the console’s temporary RAM. It was, for all intents and purposes, cloud gaming in its primitive infancy.

The service offered a rotating library of approximately 50 titles per month, including hits like Sonic the Hedgehog, early looks at upcoming releases, and unique versions of games tailored specifically for the platform. However, because the games were loaded into volatile memory and never written to a permanent storage medium like a cartridge or disc, they were inherently transient. When the console was turned off, the game vanished. When the service was shuttered in 1998, the unique code that powered the Sega Channel’s exclusive content appeared to be lost to time.

Unearthing the "Lost Levels"

The recent recovery by the VGHF has brought several high-profile "lost" games back into the light. Among the most notable is a unique version of Garfield: Caught in the Act. While the game received a standard retail release on the Genesis, the Sega Channel version featured "The Lost Levels"—content that was omitted from the physical cartridge due to storage limitations but was delivered to subscribers via the cable pipe. For twenty-five years, these levels existed only in the memories of those who played them during the service’s peak. Now, they are preserved as playable artifacts.

Similarly, the recovery includes a version of The Flintstones that was previously believed to be extinct. These aren’t just curiosities for completionists; they are essential pieces of the developmental puzzle. Many of these ROMs are prototypes or "Sega Channel Editions" that feature different difficulty balancing, unique title screens, or promotional branding that reflects the marketing strategies of the 1990s.

Beyond traditional games, the recovery has unearthed experimental software that highlights Sega’s ambition to turn the Genesis into a multi-purpose home terminal. This includes a primitive web browser designed for the console. In an era before the World Wide Web had a standardized look, this browser delivered compressed, static pages over the cable line, offering news and game tips. It was a clear signal that Sega viewed the console not just as a toy, but as a gateway to an interconnected digital future.

The Role of Corporate Memory and Private Archives

The success of this preservation project was not the result of a single "lucky find," but rather a meticulous assembly of fragments from across the globe. A critical component of the recovery involved the cooperation of former Sega employees, most notably Michael Shorrock, the former Vice President of Programming for the Sega Channel. Shorrock provided a wealth of internal documentation, memos, and technical specs that allowed archivists to reconstruct the service’s backend logic.

These documents revealed the existence of "Express Games," a planned but never-released successor to the Sega Channel that would have brought cable-based digital distribution to the PC market. This insight into "what might have been" is invaluable for industry analysts. It demonstrates that the transition to digital-first ecosystems was a long-term strategic goal for Sega, thwarted only by the limitations of 1990s infrastructure and the high costs of maintaining a proprietary cable network.

The recovery process also relied on "community archaeology." Dedicated researchers tracked down development hardware and specialized "test cartridges" that had been sitting in attics or private collections for decades. Because the Sega Channel used a proprietary encryption and delivery method, simply finding the hardware wasn’t enough; the team had to reverse-engineer the way the data was packaged to make the ROMs functional in a modern emulation environment.

Preservation as a Counter to "Digital Decay"

The recovery of the Sega Channel library arrives at a pivotal moment for the video game industry. A 2023 study by the Video Game History Foundation revealed a staggering statistic: 87% of classic video games released before 2010 are "critically endangered," meaning they are not in active distribution and are at risk of being lost due to hardware failure or the expiration of digital licenses.

The Sega Channel represents the "Patient Zero" of this preservation crisis. It was the first major service where the consumer owned nothing and the software existed only as long as the provider chose to keep the servers running. Today, as the industry moves toward a "subscription-only" model—exemplified by Xbox Game Pass and PlayStation Plus—the lessons of the Sega Channel are more relevant than ever. When a modern digital storefront closes, or a game is removed from a streaming service due to licensing disputes, it faces the same "ephemeralization" that claimed the Sega Channel library in 1998.

This recovery proves that with enough institutional will and technical expertise, even "lost" digital software can be reclaimed. However, it also serves as a warning. The Sega Channel recovery took twenty-five years of detective work to save 144 games. In an era where thousands of digital-only titles are released every year, the scale of the preservation challenge is growing exponentially.

The Technological Legacy and Future Trends

From a technical standpoint, the Sega Channel was a masterclass in optimization. The archivists found that Sega’s engineers had developed sophisticated compression algorithms to ensure that games could be "pushed" through the cable spectrum without interfering with television signals. This expertise in data management would eventually become the bedrock of the modern internet.

Looking forward, the recovery of these ROMs will likely spark a renewed interest in the "pre-history" of the internet. As we move toward a future dominated by 5G, cloud computing, and the "Metaverse," the Sega Channel stands as a testament to the fact that the ideas driving today’s tech giants were being tested in the mid-90s on 16-bit hardware.

Furthermore, the VGHF’s work highlights the need for better legislative protection for game preservation. Currently, archivists often operate in a legal gray area, navigating complex copyright laws that were written for physical books, not ephemeral digital broadcasts. The successful reconstruction of the Sega Channel’s history provides a powerful argument for why historians need the legal right to circumvent obsolete digital locks to save our shared cultural heritage.

Conclusion: A Victory for Cultural Heritage

The restoration of the Sega Channel’s lost library is more than a technical achievement; it is an act of cultural reclamation. Video games are the defining medium of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and the Sega Channel was the industry’s first bold step into the digital unknown. By saving these 144 ROMs, the Video Game History Foundation has ensured that future generations of designers, historians, and players can study the origins of the digital revolution.

As the industry continues its inexorable march toward a future of streaming and "software as a service," the story of the Sega Channel serves as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale. It reminds us that innovation often outpaces the infrastructure intended to support it, and that without a concerted effort to preserve our digital footprints, the most groundbreaking moments in technology can vanish as quickly as a signal on a cable line. For now, the 16-bit cloud has been brought back to earth, and the "lost levels" of gaming history are finally home.