The digital security landscape is facing a new, insidious threat delivered via the very conduits users trust most for productivity: browser extensions. Researchers have uncovered an emerging Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) operation, tracked under the moniker ‘Stanley,’ which explicitly markets a highly concerning capability: guaranteeing the successful publication of malicious browser extensions onto the official Chrome Web Store. This service fundamentally challenges the integrity of one of the world’s largest software distribution platforms, leveraging automation and evasion techniques to bypass established security vetting procedures.

The discovery, brought to light by analysts at Varonis, centers on an operator using the alias ‘Stanley.’ This service isn’t just offering pre-packaged malware; it provides a comprehensive package designed to execute sophisticated phishing attacks directly within the user’s browsing session. The core functionality revolves around intercepting user navigation and deploying an intrusive, full-screen iframe overlay. This iframe, controlled remotely by the attacker, presents content of the operator’s choosing—typically a credential harvesting form designed to mimic a legitimate site—while crucially leaving the browser’s address bar displaying the URL of the trusted, legitimate website. This visual deception is the lynchpin of the attack, exploiting the user’s reliance on the visible URL for authenticity confirmation.

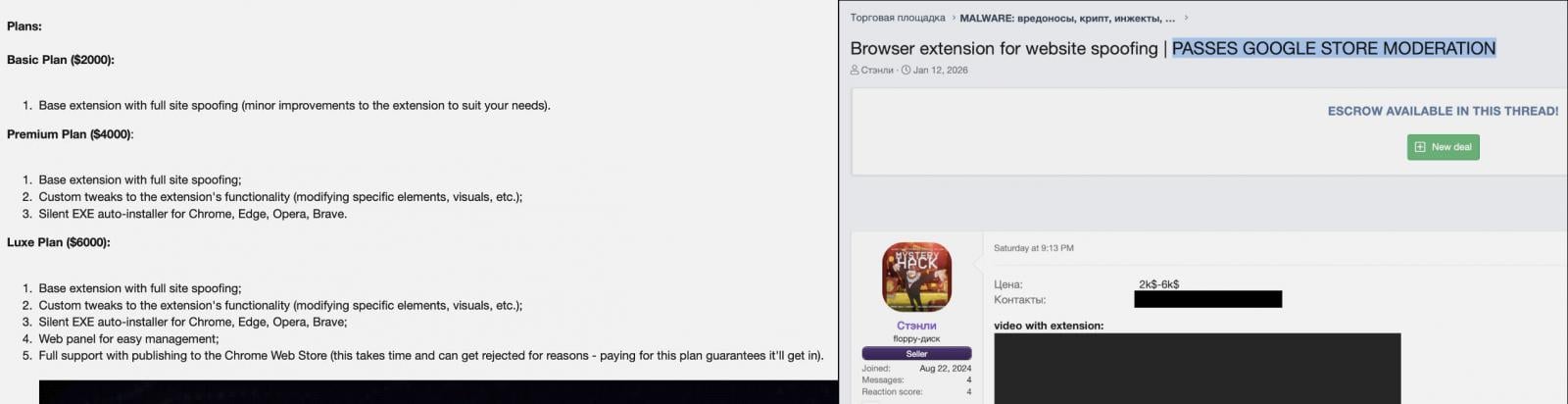

Stanley’s marketing materials, observed circulating within cybercrime forums, highlight a comprehensive suite of features tailored for efficiency and persistence. Beyond the core iframe overlay, the MaaS promises seamless, silent auto-installation across major Chromium-based browsers, including Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Brave. Furthermore, subscribers gain access to customization options, allowing threat actors to tailor the attack vectors to specific targets or campaigns.

The monetization model for Stanley mirrors traditional Software-as-a-Service structures, featuring tiered subscriptions. The most premium offering, referred to as the ‘Luxe Plan,’ appears to be the most attractive to sophisticated operators. This tier bundles the automated extension publishing support—the service’s main draw—along with a dedicated web control panel for real-time management of deployed malware. The promise of navigating Google’s review gates successfully is the primary value proposition driving adoption for this MaaS.

The Mechanism of Deception and Persistence

The technical execution described by Varonis focuses on an elegant, albeit malicious, manipulation of the user interface. The method relies on injecting code that triggers the overlay immediately upon certain navigation events. By maintaining the integrity of the address bar—the primary indicator users rely on to confirm they are on the correct domain—Stanley effectively creates a perfect, localized man-in-the-middle scenario within the browser window itself. Users might input sensitive information, such as banking credentials or corporate SSO tokens, directly into the deceptive form, believing they are interacting with the authentic service.

The operational flexibility offered by Stanley extends to sophisticated targeting and control. Operators can define specific rules based on IP addresses, enabling highly focused geographic targeting or restricting attacks to specific organizational networks. This level of granularity is crucial for high-value targets, allowing threat actors to maximize resource efficiency. Moreover, the system supports session and device correlation, meaning if a victim interacts with the phishing prompt across multiple sessions or devices, the attacker gains a richer profile of the compromised user.

To ensure operational longevity and resilience against digital countermeasures, Stanley incorporates robust command-and-control (C2) mechanisms. The extension reportedly polls its C2 server every ten seconds, ensuring that instructions are delivered rapidly. Crucially, the service employs backup domain rotation. This technique allows the malicious extension to pivot to a new, pre-registered C2 domain if the primary one is identified and taken down by security researchers or platform administrators, significantly increasing the lifespan of deployed malware.

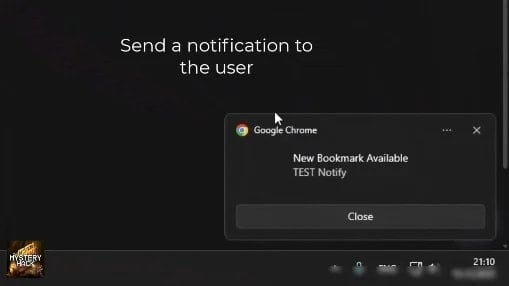

The platform also enables aggressive user engagement tactics, such as the ability to push custom browser notifications directly to the victim’s device. These notifications can be used as an auxiliary vector to lure users toward the compromised web page or to deliver urgent-sounding alerts that prompt immediate, careless action, thereby accelerating the phishing process.

Technical Assessment vs. Distribution Model

Interestingly, while the distribution strategy of Stanley is groundbreaking in its audacity, security researchers note that the underlying malware techniques are not novel. Varonis suggests that the code quality is surprisingly "rough" in places, featuring legacy programming artifacts such as Russian-language comments, the inclusion of empty error-handling blocks (catch blocks), and general inconsistencies in error management. From a pure code complexity standpoint, Stanley is described as employing straightforward, well-established methods for achieving its objective.

This dichotomy—technically unsophisticated code bundled with a sophisticated distribution promise—is what elevates Stanley’s threat profile. The true innovation here is not in the malware payload itself, but in the MaaS provider’s claimed ability to consistently circumvent the Google Chrome Web Store’s automated and manual security reviews.

Industry Implications: Trust in the Ecosystem

The implications for the browser extension ecosystem are severe. The Chrome Web Store hosts millions of extensions, many of which are essential tools for businesses and individual users. The platform’s inherent trustworthiness is predicated on Google’s vetting process. If a MaaS can reliably sell a service guaranteeing publication on this store, it suggests a significant vulnerability in Google’s defense layers, potentially leading to a massive influx of high-efficacy phishing tools disguised as legitimate add-ons.

For enterprise security, this presents a critical blind spot. Corporate security policies often whitelist specific, well-known extensions. An extension approved by Google—even if malicious—may bypass network-level checks that look for blacklisted software. Furthermore, users, conditioned to trust software sourced directly from the official store, are less likely to scrutinize permissions or publisher identity, making them prime targets.

This development underscores a broader trend in cybercrime: the professionalization and modularization of attack infrastructure. MaaS offerings lower the barrier to entry for aspiring cybercriminals. An individual with limited coding skills can purchase the "Stanley" package, effectively buying an established delivery mechanism that solves the most challenging part of the attack chain—initial distribution through a trusted channel.

The Evasion Challenge: How Does Stanley Bypass Review?

The central question surrounding Stanley is the mechanism by which it evades detection. Google utilizes a combination of static code analysis, dynamic execution analysis (sandboxing), and manual review for suspicious submissions. Malicious extensions typically fail these reviews by containing obvious indicators like heavy obfuscation, known malicious API calls, or code that attempts immediate external communication upon installation.

Stanley’s success likely hinges on one of two scenarios, or a combination thereof:

.jpg)

- Delayed Payload Execution: The extension may pass initial automated reviews because the truly malicious code—the iframe injector—is not immediately apparent or is only activated after a significant delay, after the extension has been approved and installed. This technique is often called "time-bombing" or "dormant code." The extension might perform benign actions for days or weeks before initiating the phishing overlay.

- Code Polymorphism and Obfuscation: While the underlying code might be "rough," the version submitted to Google might employ sophisticated, transient obfuscation techniques specifically designed to fool automated scanners. Once installed, the code might decrypt or unpack the true payload using a mechanism that doesn’t trigger static analysis flags during the review phase.

Recent security reports, such as those from Symantec and LayerX, have repeatedly documented campaigns involving malicious Chrome extensions that manage to survive platform scrutiny, often by hiding sophisticated behaviors related to credential theft or data exfiltration. Stanley appears to be commercializing the successful exploitation of these ongoing gaps.

Mitigation and Future Trends

The emergence of Stanley necessitates a proactive shift in user and organizational security posture. Relying solely on platform vetting is no longer sufficient.

For end-users, the advice remains prudent but requires greater emphasis: the principle of least privilege must be strictly applied to extensions. Users should audit their installed extensions regularly, remove any that are rarely used, and scrutinize publisher reputations closely, even when the extension is listed on the official store. Reviews must be read critically, looking for recent, suspiciously positive feedback or mentions of unexpected behavior.

For organizations, the need for endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions capable of monitoring browser activity is paramount. Tools must look beyond simple application blacklisting to detect behavioral anomalies, such as an extension injecting content over an existing domain’s rendering context. Furthermore, organizations should consider implementing policies that restrict the installation of any extension not explicitly vetted and approved by IT security teams.

Looking ahead, the arms race between MaaS providers like Stanley and platform gatekeepers like Google will intensify. We can anticipate several trends:

Firstly, expect an increase in specialized MaaS offerings focused solely on evading specific sandbox environments. If Google tightens its review process for static code, we will see more MaaS solutions focusing on dynamic execution camouflage or leveraging zero-day vulnerabilities in the browser engine itself, moving beyond simple extension APIs.

Secondly, the rise of multi-browser MaaS offerings, like Stanley’s support for Edge and Brave, indicates a strategic move by cybercriminals to diversify their attack surface across the Chromium ecosystem, which shares underlying security frameworks.

Finally, the concept of "trusted distribution" is eroding. Security professionals must increasingly treat all third-party code—regardless of its source—with inherent suspicion, shifting the burden of verification from the platform distributor back to the end-user and their security tooling. The Stanley MaaS is a stark reminder that the most effective malware leverages legitimate infrastructure to deliver its payload, making visibility and behavior monitoring the ultimate defenses.

In response to these evolving threats, platform providers are under immense pressure to innovate their defense mechanisms. This likely includes more aggressive use of machine learning to profile extension behavior post-installation, rather than relying solely on pre-submission checks. However, as long as there is a lucrative market for easy, guaranteed access to millions of users, innovative, albeit malicious, MaaS solutions will continue to surface.