The intensifying climate crisis has precipitated a dangerous convergence of meteorological extremes and systemic infrastructure strain, fundamentally altering global energy consumption patterns. The summer seasons of the mid-2020s served as a critical inflection point, marked by catastrophic heatwaves that crippled power distribution networks across industrialized regions—from the sprawling grids of North America and the densely populated urban centers of Europe to the hyper-arid landscapes of the Middle East. As ambient temperatures soar, the reliance on active cooling—specifically electrically driven air conditioning (AC)—skyrockets, creating a vicious feedback loop. Increased demand for cooling necessitates increased power generation, which often involves burning fossil fuels, further accelerating global warming and intensifying the strain on vulnerable electrical infrastructure. This energy-intensive cycle highlights an urgent need for revolutionary, non-powered thermal management solutions.

The answer to this modern dilemma lies in resurrecting and scientifically perfecting a principle as old as human civilization: radiative cooling. This passive process, which requires zero energy input, involves optimizing materials to scatter incoming solar radiation while simultaneously maximizing the emission of internally absorbed heat away from the surface and directly into the cold expanse of deep space.

Qiaoqiang Gan, a distinguished professor of materials science and applied physics at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, underscores the ubiquity of this phenomenon. "Radiative cooling is universal—it exists everywhere in our daily life," he explains. The cooling effect is most easily observed nocturnally. Any object exposed to the clear night sky, such as a metal vehicle roof, will radiate heat into the atmosphere, often cooling its surface several degrees below the ambient air temperature. This temperature differential is precisely what causes dew formation—a visible manifestation of the natural thermal dissipation process.

Historically, various cultures have intuitively leveraged this thermal physics. Ancient civilizations in regions like Iran, North Africa, and the Indian subcontinent perfected passive cooling techniques, notably the construction of yakhchals (ancient ice houses) and the simple, yet effective, practice of manufacturing ice by exposing shallow water pools to clear desert skies overnight. More broadly, traditional architecture utilized thick walls and reflective, light-colored roofing materials—the progenitors of the modern "cool roof"—to minimize solar heat gain and maintain comfortable interior temperatures.

Aaswath Raman, a materials scientist at UCLA and cofounder of the pioneering radiative-cooling startup SkyCool Systems, notes that humans have exploited this inherent effect, whether through empirical knowledge or deliberate engineering, for millennia. However, the scientific pursuit in the 21st century has been focused on transcending the limitations of nocturnal cooling and achieving effective daytime radiative cooling (DRC).

The major hurdle for passive cooling during the day is the intense solar irradiance that constantly bathes the surface. To cool below the ambient temperature under full sunlight, a material must exhibit two critical properties simultaneously: high solar reflectance (ideally reflecting nearly 100% of the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) and high thermal emissivity within a very specific wavelength range.

This specific range is known as the "atmospheric window," which spans infrared wavelengths between approximately 8 and 13 micrometers. This band is crucial because the gases in Earth’s atmosphere (like water vapor and carbon dioxide) are largely transparent to radiation in this spectrum. Heat radiated at these specific wavelengths bypasses atmospheric absorption and escapes directly into space, essentially using the cosmos as a massive, infinite heat sink.

The breakthrough moment occurred in 2014 when Raman and his collaborators demonstrated the first practical DRC film. By customizing multi-layered photonic structures—essentially engineered mirrors—they created a surface that both rejected the entire solar spectrum and emitted thermal energy precisely through the atmospheric window. These films successfully achieved cooling of up to 9°F (5°C) below the ambient air temperature, even in direct sunlight, proving that non-evaporative, zero-energy cooling was feasible for modern structures.

While these early photonic films provided the essential proof of concept, their complexity and cost posed significant challenges for mass commercialization. The current trajectory of the industry, as noted by Raman, has shifted toward more robust, scalable, and cost-effective material science solutions. The emphasis is now on leveraging sophisticated composite materials, including specialized ceramic compounds, engineered nanostructure coatings, and highly reflective polymer matrices. These materials prioritize broad-spectrum solar scattering, aiming for high total solar reflectance (TSR) across all incoming wavelengths, which provides excellent bulk cooling performance while simplifying the manufacturing process compared to highly tuned photonic stacks.

The global market for advanced cooling solutions is entering a period of intense competition. Startups like SkyCool, Planck Energies, Spacecool (which recently featured its technology at Japan’s Expo 2025 pavilion), and i2Cool are engaged in a race to optimize materials that can consistently reflect over 94% of incident sunlight in temperate or arid environments, pushing above 97% TSR in more challenging, humid tropical climates where absorption risk is higher.

The economic implications are profound. Cooling accounts for a substantial fraction of global energy consumption, often exceeding 15% of all electricity used worldwide. By integrating these high-performance coatings, commercial and residential buildings can dramatically reduce their reliance on mechanical compression-based HVAC systems. Early pilot projects—ranging from California supermarket rooftops seeking energy efficiency improvements to residential developments integrating these coatings—have demonstrated tangible energy savings, with reductions in AC energy demand often falling between 15% and 20%.

This is not merely a marginal improvement; it represents a significant opportunity for load balancing in strained electrical grids. During peak heat events, when the margin between supply and demand is narrowest, widespread deployment of radiative cooling materials acts as a distributed energy management system, passively reducing peak load and preventing the cascading failures seen in recent heatwave scenarios.

The industry implications extend far beyond traditional construction. Radiative cooling coatings are poised to transform critical infrastructure sectors. Data centers, which generate massive amounts of waste heat and require immense energy for cooling, stand to benefit tremendously. By coating the exterior surfaces of these facilities, operators can achieve lower internal thermal loads, improving server efficiency and reducing operational expenditure. Furthermore, urban heat island mitigation is a major application. Coating roads, sidewalks, and parking lots with these high-reflectivity materials can lower localized ambient temperatures, making cities more livable and further reducing the energy required for cooling surrounding buildings.

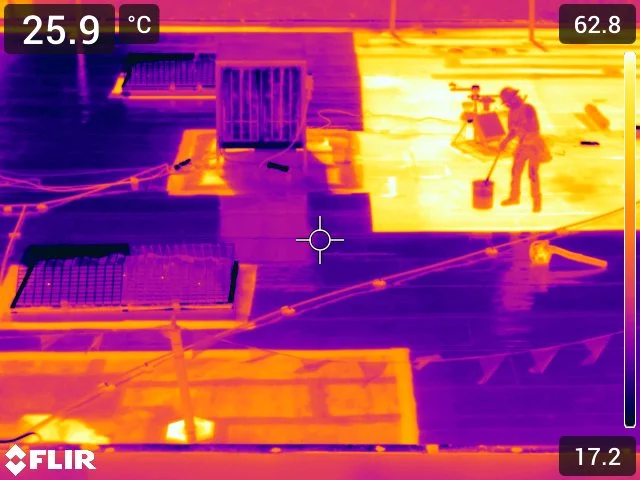

The innovation also drives progress in the field of "personal thermal management." Professor Gan highlights the potential for moving beyond macro-level structural applications to micro-level wearable technology. Researchers are developing advanced, reflective textiles designed to be incorporated into sportswear, industrial uniforms, and military gear. These garments are engineered to passively reject body heat and solar load, offering direct thermal relief to individuals exposed to extreme heat stress. This application is crucial for occupational health and safety in industries like construction, agriculture, and emergency services.

Despite the monumental potential, the path to widespread adoption is fraught with material science and sustainability challenges. Radiative cooling materials, much like solar photovoltaic panels, are subject to environmental degradation. Their performance is inherently tied to their surface integrity. Accumulation of dust, grime, and air pollution, known as "soiling," severely diminishes reflectivity over time, requiring consistent maintenance or the development of self-cleaning functionalities. Furthermore, the inherent vulnerability to weather—specifically cloud cover—means that performance fluctuates, preventing these materials from serving as a sole, continuous cooling source.

The most pressing challenge, however, centers on durability and chemical safety. To achieve the required long-term resilience against UV radiation, moisture, and abrasion, the current generation of the cheapest and highest-performing cooling materials often relies on fluoropolymers, commonly known as PFAS or "forever chemicals." These compounds, prized for their exceptional chemical stability and weather resistance, are non-biodegradable and pose long-term environmental and health risks.

Raman acknowledges this critical tension: "These fluoropolymers represent the best class of products that tend to survive outdoors with the required high-performance characteristics. For long-term scale-up, the question is whether we can maintain the durability and hit this low cost point without materials like those."

This challenge has galvanized a significant research pivot toward developing robust, bio-friendly, and non-toxic polymer and ceramic composites. The next wave of innovation focuses on creating inorganic, highly crystalline white pigments and proprietary polymer binders that can mimic the resilience of fluoropolymers while adhering to stricter environmental standards. Successfully decoupling high performance from chemical persistence is essential for securing regulatory approval and public acceptance for mass deployment globally.

Regulatory frameworks are also catching up to the technology’s potential. Jurisdictions like California, with aggressive energy efficiency codes such as Title 24, are increasingly integrating cool roof standards, which creates a market pull for high-reflectance materials. However, the adoption of advanced DRC technologies that cool below ambient temperature requires updates to existing building codes and certification processes that currently focus primarily on heat rejection rather than active dissipation into space.

Ultimately, while radiative cooling represents a paradigm shift in passive thermal management, experts maintain a balanced perspective. As Professor Gan prudently advises, "We cannot be overoptimistic and say that radiative cooling can address all our future needs. We still need more efficient active air-conditioning systems." Radiative cooling is best viewed not as a replacement, but as a critical complementary technology. By minimizing the heat load on structures, these smart surfaces can significantly downsize the necessary capacity of active AC systems, leading to lower capital costs, reduced energy consumption, and substantially decreased carbon footprints. The fusion of millennia-old principles with cutting-edge nanophotonics and sustainable chemistry is charting a vital course toward a future where comfort and environmental responsibility are mutually reinforcing goals.