The digital security landscape has witnessed a sophisticated escalation in browser-based social engineering, exemplified by the recent emergence of an extension dubbed ‘NexShield.’ This application, masquerading as a high-performance, privacy-focused ad blocker for both Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge, employs a novel denial-of-service (DoS) technique to manipulate users into executing arbitrary code. The core of this campaign hinges on creating a severe, tangible disruption—a genuine browser crash—to pivot into a classic ClickFix malware delivery mechanism, ultimately targeting endpoints with a new remote access tool tailored for corporate infiltration.

The deceptive nature of NexShield is amplified by its calculated impersonation. Researchers observing the campaign noted that the extension was deliberately branded with the name and ethos of Raymond Hill, the acclaimed original developer behind the highly trusted uBlock Origin, a legitimate extension boasting a massive user base exceeding fourteen million. This calculated misappropriation of developer credibility provides an immediate, albeit false, sense of security, encouraging widespread installation before the malicious payload is activated. Although platform providers have since purged NexShield from the official Chrome Web Store, the initial dissemination vector highlights a persistent vulnerability in the extension vetting processes, particularly those relying on developer reputation.

The mechanics of the initial disruption are technically noteworthy. Security analysts from the managed security service provider Huntress detailed how NexShield weaponizes standard browser functionalities. Specifically, the extension initiates an endless loop of chrome.runtime port connections. This aggressive resource consumption quickly saturates the browser’s memory allocation, leading to a cascade failure characterized by frozen tabs, spiking CPU utilization within the browser process, and substantial RAM bloat. The inevitable outcome is a complete browser hang or crash, forcing the end-user to manually terminate the application via the Windows Task Manager. Huntress has aptly categorized this specific initial stage as ‘CrashFix,’ distinguishing it from earlier ClickFix variants that relied on visual deception, such as simulated Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) screens, because the CrashFix method delivers a verifiable, undeniable system failure.

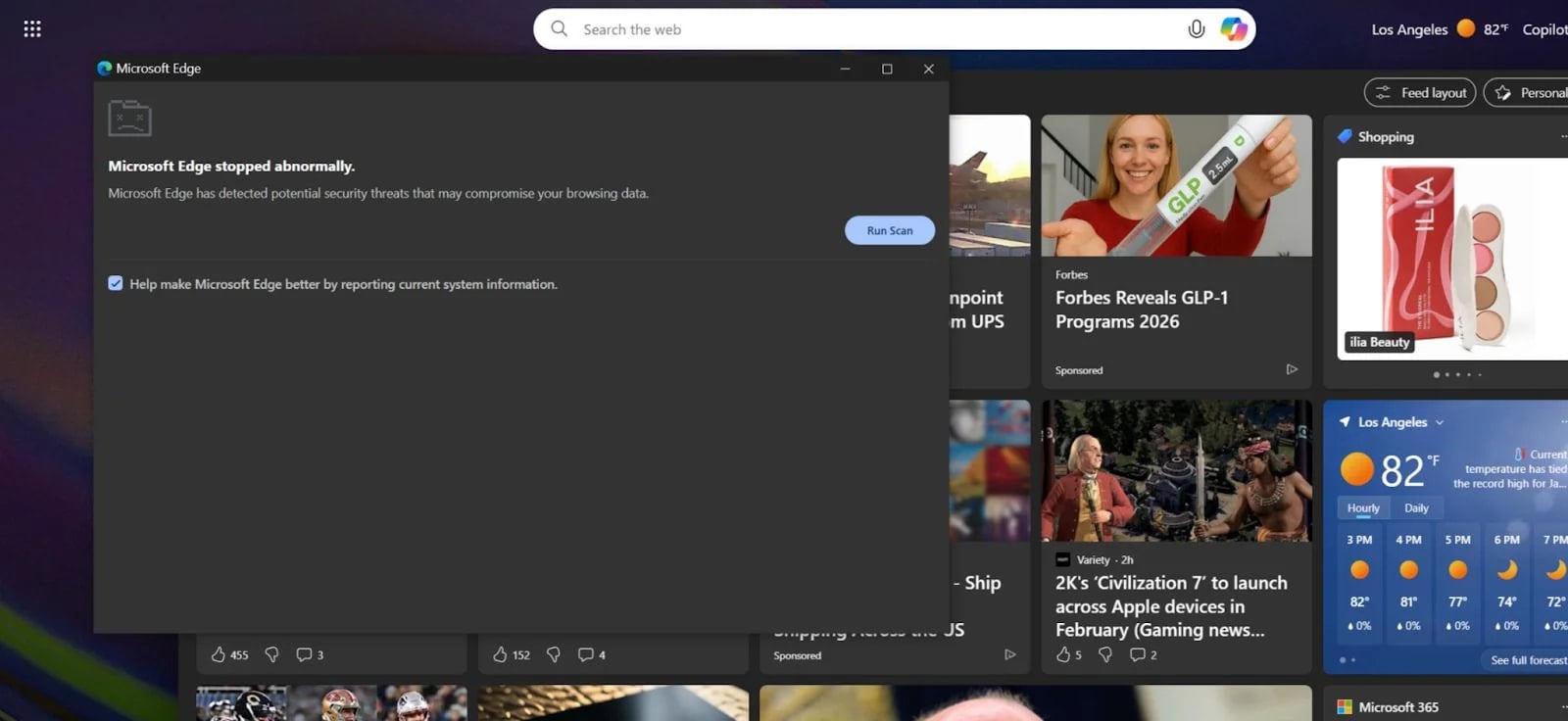

This forced system interruption is not the end goal, but the critical enabler for the next phase. Upon restarting the browser—a natural reaction following a crash—the user is immediately confronted with a convincing, malicious pop-up. This interface mimics a system diagnostic tool, warning the user of grave security breaches detected and offering a remedial "scan" to isolate the problem. This fear-driven prompt steers the user directly into the ClickFix execution pipeline.

In a textbook ClickFix maneuver, the subsequent window provides instructions that are alarmingly simple: execute a provided command line string within the Windows Command Prompt. Crucially, the malicious extension typically copies this string directly to the user’s clipboard, lowering the friction for execution to a mere Ctrl+V followed by hitting ‘Enter.’ This command sequence is meticulously engineered; it does not execute malware locally but rather acts as a retriever, initiating an obfuscated PowerShell script over a remote connection. This remote script then downloads and executes the final, true malicious payload.

A key element of evasion employed by the attackers is a deliberate time delay. To further dissociate the initial installation (the seemingly benign ad blocker) from the subsequent malicious command execution, the payload deployment is often programmed with a 60-minute latency following NexShield’s installation. This delay is intended to confound forensic analysis and bypass automated, near-term behavioral monitoring tools that might flag immediate post-installation activity.

The ultimate objective of this infection chain appears bifurcated, tailored distinctly based on the target environment. For endpoints within corporate domains—meaning machines joined to organizational Active Directory structures—the threat actor is deploying a newly observed Remote Access Trojan (RAT) named ModeloRAT. This tool exhibits significant sophistication, designed for persistent infiltration and lateral movement within enterprise networks. ModeloRAT’s capabilities are extensive, encompassing detailed system reconnaissance (fingerprinting hardware, software, and network configurations), the ability to execute arbitrary PowerShell commands remotely, deep interaction with the Windows Registry for persistence establishment, the injection of secondary, more specialized malware payloads, and the capacity for self-updating to adapt to defensive measures. This focus strongly suggests that the primary target of this particular iteration is corporate espionage or ransomware deployment within lucrative organizational infrastructures.

Conversely, for non-domain-joined hosts—typically personal computers utilized by home users—the command and control (C2) server delivered a distinctly less threatening response: a simple text message reading "TEST PAYLOAD!!!!" According to Huntress researchers, this suggests that home users may be considered a lower priority, potentially serving as a proving ground for the malware infrastructure, or indicating that the threat actor is prioritizing the refinement of their enterprise attack infrastructure before deploying the full ModeloRAT toolkit against consumer targets.

This ‘CrashFix’ variant stands in stark contrast to preceding ClickFix campaigns. Earlier iterations, such as one documented recently by Securonix, relied on visual trickery, leveraging the browser’s full-screen API to generate a convincing, but fake, Windows BSOD screen to frighten users into action. The brilliance, and danger, of CrashFix lies in its use of actual system instability. When a user witnesses their entire browser application forcibly terminate due to resource exhaustion, the perceived threat level is significantly higher, making them far more susceptible to following the subsequent, seemingly urgent, instructions to "fix" the problem.

The technical deep dive provided by the security researchers illuminates the multi-stage nature of this threat. The infection chain is complex, moving from initial deceptive installation, through engineered DoS, social engineering via the prompt, elevated privilege command execution via PowerShell, and culminating in the establishment of persistent remote control via ModeloRAT. Understanding the capabilities of ModeloRAT is crucial for incident response. Its ability to fingerprint systems and ascertain privilege levels allows the threat actor to tailor subsequent actions—whether escalating privileges, mapping internal network shares, or establishing long-term persistence mechanisms like scheduled tasks or modified startup entries.

The attribution of this specific campaign, according to Huntress analysis, points toward a threat actor group designated ‘KongTuke.’ This actor has been under surveillance since early 2025, suggesting a period of infrastructure development and refinement. The shift in focus evidenced by the deployment of a sophisticated RAT like ModeloRAT in enterprise environments signals an evolution in KongTuke’s operational strategy. Cybercriminals are increasingly recognizing the substantial financial rewards associated with targeting well-resourced organizations, necessitating more advanced, multi-stage delivery mechanisms like CrashFix to bypass standard security hygiene.

The broader industry implications of the CrashFix campaign are significant, touching upon the inherent security risks embedded within the extension ecosystem. Browser extensions, while offering essential functionality, represent a significant expansion of the application attack surface. They possess broad permissions, often granting access to browsing history, cookies, and, critically, the ability to interact with the underlying operating system via command execution APIs. The NexShield incident underscores that trust-based vetting is insufficient; platforms must implement more rigorous, dynamic analysis of extension behavior, especially concerning resource consumption and communication patterns that might indicate covert DoS mechanisms.

For IT and security professionals, the lessons learned from CrashFix are manifold. Prevention hinges on strict adherence to security fundamentals. Users must be educated to critically evaluate the provenance of any browser extension, prioritizing those from established, verified publishers, and avoiding applications that promise suspiciously high performance or privacy gains, especially if they leverage social engineering tactics related to developer fame. Furthermore, enterprise environments must enforce strict application whitelisting policies, ideally restricting users from installing extensions altogether unless explicitly sanctioned and vetted by the security team.

Crucially, the remediation process following a successful ClickFix infection is more involved than simply removing the offending extension. As observed, uninstalling NexShield does not inherently sanitize the system of subsequent payloads. If a user executed the command prompt instruction, ModeloRAT or other scripts have already established persistence on the host. Consequently, any system confirmed to have run the malicious command requires a comprehensive forensic cleanup, including scans for newly created persistence mechanisms, registry modifications, and verification that the ModeloRAT implant has been fully eradicated from the system’s memory and storage. This underscores the necessity for robust Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions capable of tracking command-line activity and process lineage, rather than merely relying on file signatures.

Looking ahead, this trend suggests a future where malware leverages increasingly complex, seemingly benign software interactions to generate disruptive preconditions for attack. We may see further evolution away from simple visual hoaxes towards engineered system instability, exploiting the assumption that legitimate software occasionally fails. As LLM integration continues to redefine digital tools, the security community must remain vigilant against these "trust-based" attacks that weaponize user confidence in established digital tools to breach corporate defenses. The evolution from simple adware delivery to deploying sophisticated RATs via a deliberately crashed browser illustrates a maturing threat actor prioritizing deep, persistent access over transient monetization.