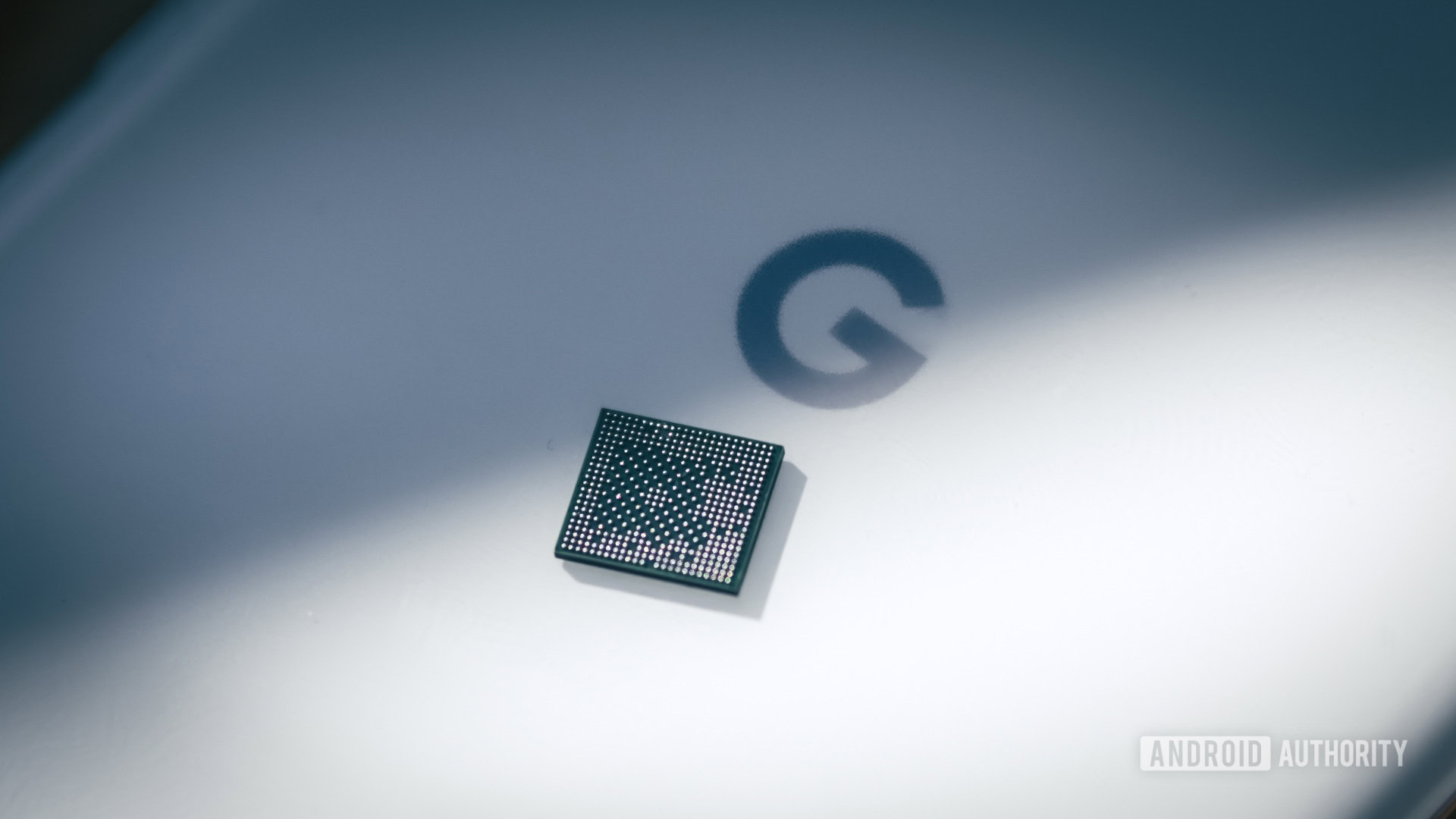

The advent of specialized silicon for artificial intelligence processing within smartphones, marked notably by the introduction of the Huawei Mate 10’s Kirin 970 and its integrated Neural Processing Unit (NPU) roughly eight years ago, represented a seminal moment in mobile computing. This hardware shift signaled a broad industry consensus that sophisticated, low-latency, on-device AI was not just a futuristic concept but an imminent reality. Today, this consensus is ubiquitous: from Arm detailing future architecture roadmaps to Qualcomm and Apple embedding increasingly powerful accelerators, the prevailing industry narrative champions local AI processing as the fundamental driver of next-generation mobile experiences. Even Google has committed heavily to this trajectory with its custom Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) designs integrated into its Pixel lineup, leveraging them for everything from advanced computational photography to real-time language processing.

Despite this sustained hardware investment and vocal industry commitment, the realized potential of on-device AI remains conspicuously constrained. Consumers interact with a finite, curated set of features—largely those developed internally by Google—while a truly vibrant, creative third-party development ecosystem for local ML remains elusive. The irony is sharp: the specialized hardware built specifically to enable this future—the NPU—is itself a primary constraint, not due to technical inadequacy, but because it has fundamentally failed to mature into an accessible, standardized platform. This disconnect forces a critical examination: what is the actual utility of this high-performance, yet largely siloed, silicon residing within our pocket supercomputers?

Deconstructing the Purpose of the NPU

To understand the platform stagnation, one must first define the function of the Neural Processing Unit. In the heterogeneous computing environment of a modern System-on-a-Chip (SoC), the NPU occupies a niche distinct from the Central Processing Unit (CPU) and the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). While the CPU manages general application logic and sequential tasks, and the GPU excels at massive parallel rendering pipelines, the NPU is a specialized engine engineered for the mathematics central to machine learning inference.

Specifically, NPUs are optimized for the highly parallelized matrix operations—such as fused multiply-add (FMA) and fused multiply-accumulate (FMAC)—that underpin neural network calculations. Crucially, they excel at handling extremely low-precision data formats, often down to 4-bit or even 2-bit integer quantization (INT4 or lower). This precision level is challenging for general-purpose cores to manage with the necessary speed and power efficiency. The NPU’s architecture is tailored to these specific memory access patterns and data types, allowing it to execute complex inference models far more rapidly and with significantly lower power consumption than either the CPU or GPU might achieve for the same task. This efficiency gain is paramount in battery-constrained mobile devices; no manufacturer desires their flagship AI feature to drain the battery in minutes.

The GPU Analogy: Why Mobile AI Diverges from Desktop Powerhouses

The conversation around high-performance computing often points toward the massive parallel processing capabilities of discrete GPUs, exemplified by NVIDIA’s offerings. Desktop GPUs, especially those utilizing architectures like CUDA with dedicated Tensor Cores, have become the bedrock of cloud-based Large Language Model (LLM) training and inference. Their effectiveness stems from extreme parallelism across numerous processing units and robust support for diverse data formats used in cutting-edge models.

However, the physics of mobile design impose severe limitations that differentiate mobile GPUs (like Arm Mali or Qualcomm Adreno) from their desktop counterparts. Mobile GPUs are fundamentally constrained by thermal envelopes and strict power budgets. Their architecture prioritizes efficiency over raw throughput, often employing techniques like tile-based rendering pipelines that are excellent for graphics workloads but suboptimal for sustained, monolithic compute tasks inherent in deep learning inference. While modern mobile GPUs possess capabilities for handling 16-bit and increasingly 8-bit floating-point (FP16/INT8) operations—formats more complex than the extreme quantization NPUs target—they lack the specialized instruction sets and optimization hooks for the absolute lowest precision models needed for true edge deployment of massive models.

This brings the discussion back to software exposure. Desktop AI development largely coalesced around NVIDIA’s CUDA ecosystem. CUDA offers developers unparalleled, kernel-level access to the hardware, enabling meticulous optimization that extracts maximum performance from the silicon. Mobile platforms, conversely, suffer from a fragmentation crisis. Each major silicon vendor—Qualcomm (Hexagon), Apple (Neural Engine), and specialized in-house efforts like Google’s Tensor—offers a proprietary NPU architecture coupled with its own vendor-specific SDK or API layer. This architectural heterogeneity means that a developer creating an optimized computer vision application for a Snapdragon chip cannot simply port that highly tuned code to an Apple Neural Engine without significant, time-consuming redevelopment and re-profiling.

The Platform Paradox: Abstraction vs. Access

The promise of dedicated mobile AI was undermined by the very mechanisms intended to standardize it. The Android Neural Networks API (NNAPI) was an attempt to create a universal interface, abstracting the differences between various NPUs, GPUs, and DSPs. Unfortunately, NNAPI’s historical implementation often standardized the interface without standardizing the underlying performance characteristics or driver reliability. As a result, performance could fluctuate wildly depending on the vendor’s driver stack interpreting the generic instructions. This unreliability, coupled with platform shifts—such as Samsung’s discontinuation of its Neural SDK and the often experimental status of Google’s own Tensor ML SDK—created an environment where many third-party developers deemed the effort required to target NPU acceleration too high a risk for uncertain returns. The consequence has been a retreat to the safer, though less efficient, CPU path or reliance on cloud services.

This fragmentation is the primary reason why, despite the horsepower present in the hardware, the software experience remains curated. Only major players with the resources to maintain specialized development teams for multiple architectures can consistently deploy cutting-edge on-device AI.

The Emergence of Runtime Standardization: LiteRT’s Pivotal Role

A significant industry inflection point may be arriving via software unification efforts, most notably Google’s introduction of LiteRT, which effectively re-positions and enhances the TensorFlow Lite runtime. LiteRT is engineered to serve as a singular, comprehensive on-device runtime capable of orchestrating workloads across the fragmented mobile hardware landscape—CPU, GPU, and vendor-specific NPUs (currently supporting key players like Qualcomm and MediaTek).

LiteRT’s strength lies in its active management of acceleration. Instead of relying on a standardized but often underperforming abstraction layer like the old NNAPI, LiteRT aims to own the execution runtime itself. This allows the software to intelligently select the most performant path for a given model operation at runtime, dynamically choosing the NPU, GPU, or CPU core best suited for the task, thereby maximizing hardware utilization regardless of the underlying silicon differences.

The ambition behind LiteRT is sweeping: to enable consistent, high-performance on-device inference across Android, iOS, and even edge/IoT environments. This approach mirrors the centralized nature of desktop frameworks, but crucially, it maintains the constraints necessary for mobile deployment. A TensorFlow Lite model, managed by LiteRT, is a pre-baked artifact where precision, quantization levels, and execution pathways are determined upfront. This predictability is essential for delivering consistent user experiences on constrained hardware, contrasting with the dynamic, highly configurable nature of cloud-based LLM pipelines.

Future Trajectories: Hardware Evolution and Software Abstraction

While LiteRT addresses the software abstraction deficit, hardware evolution continues apace, potentially reshaping the NPU’s long-term centrality. Several trends suggest the lines between processing blocks may blur:

-

CPU Augmentation: Arm’s latest CPU architectures, such as the C1 series, incorporate specialized extensions like SME2 (Scalable Matrix Extensions 2). These extensions offer substantial, sometimes fourfold, acceleration for specific ML workloads directly within the CPU pipeline, often with broader framework compatibility than proprietary NPUs. As CPUs become inherently better at vectorized and quantized math, the need for a separate, dedicated NPU block for simpler tasks diminishes.

-

GPU Reorientation: The mobile GPU market is seeing a strategic pivot toward native AI support. Reports of manufacturers like Samsung exploring custom GPU architectures are significant. If future mobile GPUs are designed from the ground up with superior support for low-bit precision math (INT8/FP8) and higher computational density—as seen in next-generation designs from Imagination Technologies (E-series)—they could naturally absorb many tasks currently relegated to the NPU, offering a better balance of graphics and compute power.

-

The Continued Role of the NPU: Despite these trends, dedicated NPUs are unlikely to vanish soon. Their extreme efficiency at ultra-low precision inference (INT4 and below) remains a crucial advantage for background tasks or highly frequent, low-impact operations where even an augmented CPU would draw too much power. NPUs will likely transition from being the gatekeeper of mobile AI to a highly specialized accelerator within the wider computational fabric.

The real metric for success in mobile AI is no longer the tera-operations per second (TOPS) rating of a specific NPU, but the robustness and reach of the software layer that manages resource allocation. If LiteRT proves successful in reliably mapping workloads to the best available hardware—whether it’s a future GPU, an advanced CPU extension, or the dedicated NPU—then the fragmentation problem dissolves.

The current situation suggests that for the vast majority of third-party applications, the integrated capabilities of the CPU and GPU—enhanced by modern instruction sets and improved quantization support—will handle the bulk of practical AI workloads. The NPU’s role will narrow to specific, power-critical niches. Ultimately, the vibrancy of the mobile AI ecosystem hinges not on the silicon specification sheet, but on the maturity of cross-platform runtimes like LiteRT. Only when developers can confidently deploy a single binary that efficiently targets the NPU acceleration on a Snapdragon device, a Tensor device, and potentially even an Apple device, will the eight-year-old promise of widespread, innovative on-device AI begin to materialize beyond the confines of the major platform holders. We are moving from a hardware arms race to a software abstraction race, and that shift is the most vital development for the next phase of mobile intelligence.