The ecosystem surrounding sophisticated malware-as-a-service (MaaS) offerings is facing unprecedented scrutiny following a targeted operation by security researchers who successfully exploited a critical vulnerability within the administrative infrastructure of the notorious StealC information stealer. This strategic maneuver, utilizing a cross-site scripting (XSS) flaw embedded within the web-based control panels utilized by StealC operators, provided the research team with a rare, deep-dive perspective into the operational habits and hardware footprints of the criminal entities leveraging this potent tool.

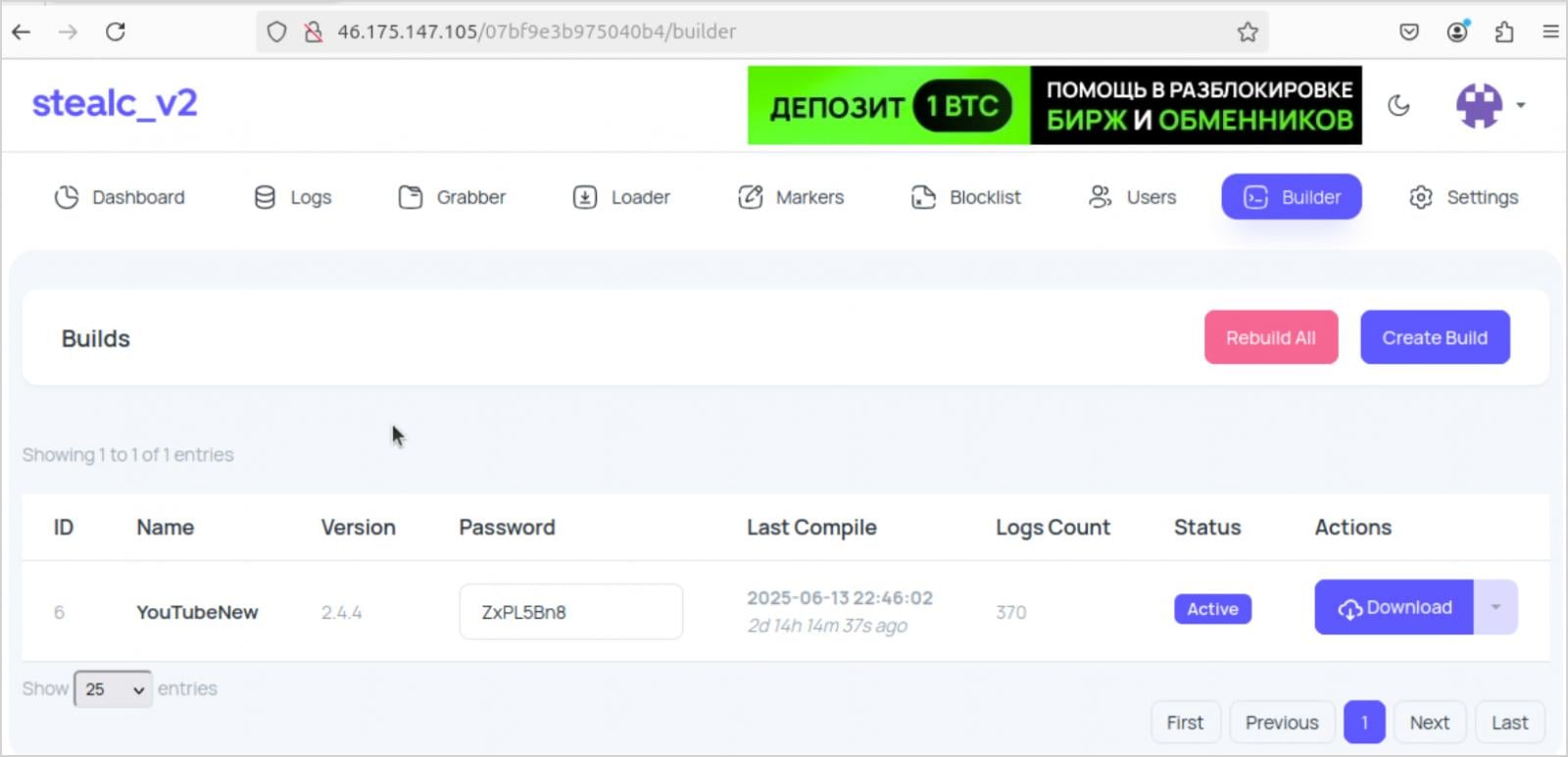

StealC first surfaced in the digital underground in early 2023, rapidly gaining notoriety across clandestine cybercrime forums due to its highly aggressive promotion and its comprehensive suite of data exfiltration capabilities. Its initial appeal lay in its ability to evade detection and systematically harvest sensitive information from compromised endpoints. As is common in the competitive MaaS landscape, the developer continually refined the product. This evolution culminated in the release of version 2.0 in April of the previous year, which introduced significant enhancements, including integration with Telegram bots for real-time incident reporting and a modernized builder utility. This builder allowed affiliates to generate tailored StealC executables based on modular templates and bespoke data-stealing directives, significantly lowering the barrier to entry for less technically proficient actors.

The research breakthrough was facilitated by a coincidental event: the source code for the malware’s administrative dashboard became publicly accessible, providing security analysts with the necessary blueprints to conduct deep-level vulnerability assessments. It was within this accessible codebase that researchers from CyberArk identified a critical XSS vulnerability residing within the panel interface itself. This flaw represented a systemic weakness in the supply chain management of the malware, turning the tool designed to steal data into a conduit for intelligence gathering on the attackers.

Exploitation of this XSS vulnerability yielded a treasure trove of operational telemetry. The researchers were able to systematically fingerprint the operators’ environments, gathering details on their web browsers, underlying hardware specifications, and even indicators related to their general geographic positioning. More critically, the vulnerability allowed for the observation of live administrative sessions and the direct exfiltration of active session cookies associated with the control panels. This capability effectively granted the researchers the keys to the kingdom, allowing them to remotely hijack ongoing sessions from their own controlled environments. As detailed in their findings, the exploitation provided "characteristics of the threat actor’s computers, including general location indicators and computer hardware details," further confirmed by the ability to "retrieve active session cookies, which allowed us to gain control of sessions from our own machines."

The researchers deliberately withheld specific technical details pertaining to the XSS payload and its precise implementation. This decision was a calculated move aimed at preventing StealC administrators from immediately patching the flaw, thereby maximizing the window for intelligence collection and operational disruption.

One of the most illuminating case studies derived from this infiltration involved a specific StealC affiliate, cryptically labeled "YouTubeTA." This actor demonstrated a sophisticated, albeit flawed, approach to distribution. YouTubeTA leveraged compromised, historically legitimate YouTube accounts—likely acquired through credential stuffing or previously successful phishing campaigns—to host and disseminate malicious links. Throughout 2025, this individual or group ran extensive campaigns, resulting in the collection of over 5,000 distinct victim logs. The aggregate data harvested included approximately 390,000 passwords and an astonishing 30 million cookies, though the majority of these cookies were assessed as non-sensitive session identifiers rather than high-value authentication tokens.

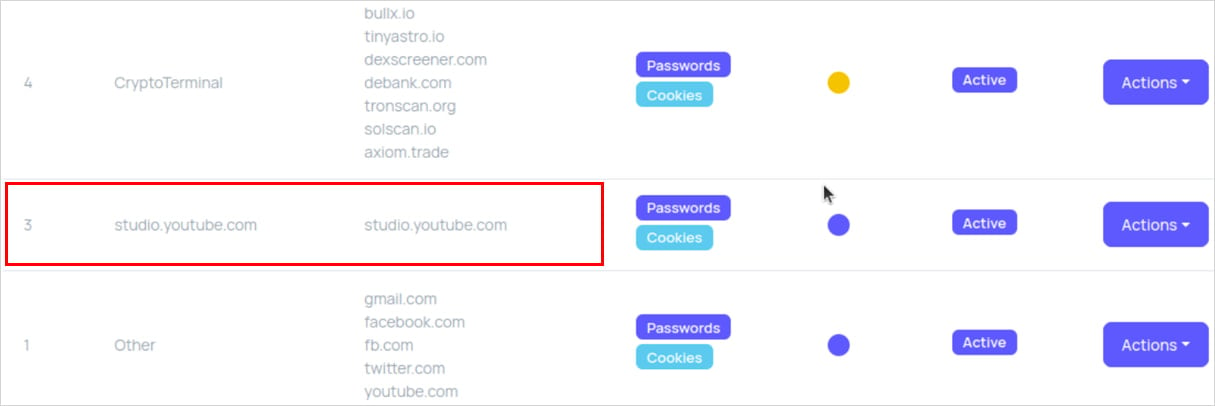

Analysis of the captured administrative panel screenshots, specifically the "Markers" page, provided insight into the social engineering vectors favored by YouTubeTA. A significant proportion of successful infections were traced back to victims actively searching for cracked or pirated versions of high-demand professional software, specifically Adobe Photoshop and Adobe After Effects. This highlights the enduring efficacy of exploiting users seeking unauthorized access to premium tools as a primary infection vector for sophisticated malware distribution.

The true intelligence coup, however, stemmed from the ability to profile the threat actor directly. By leveraging the XSS flaw, the security team deduced that the operator associated with YouTubeTA was utilizing an Apple M3-based hardware platform. Furthermore, system language settings indicated a combination of English and Russian localization, and the time zone configuration pointed toward Eastern European operational hours. The geographical link solidified when the threat actor neglected to route their administrative panel access through a Virtual Private Network (VPN), inadvertently exposing their originating IP address. This IP was subsequently traced back to the Ukrainian Internet Service Provider, TRK Cable TV. This level of detail underscores the pervasive operational security risks inherent in utilizing MaaS platforms, even for the administrators themselves.

The implications of this incident resonate deeply within the cybersecurity industry, particularly concerning the MaaS model. Malware-as-a-Service platforms are predicated on offering scalability, relative anonymity, and reduced operational overhead for their subscribers. However, as this event demonstrates, centralizing the command-and-control (C2) infrastructure—the control panel being the nexus of this centralization—creates a singular, high-value target. A vulnerability in this central hub not only exposes the data of the platform’s customers but also compromises the operational security of the service provider and, critically, the digital fingerprints of the entire user base accessing that panel. This single point of failure fundamentally undermines the security promise made by MaaS vendors to their criminal clientele.

The timing of the disclosure by CyberArk is also significant and suggests a strategic intent beyond mere academic reporting. Researcher Ari Novick indicated that the decision to publicize the XSS vulnerability now was motivated by a desire to introduce significant friction into the StealC ecosystem. This timing correlates with an observed recent surge in the number of active StealC operators. Analysts speculate that this growth might be a direct consequence of recent instability or high-profile doxxing events within rival stealer ecosystems, such as the recent publicized issues surrounding the Lumma stealer.

Novick articulated the objective: "By posting the existence of the XSS we hope to cause at least some disruption in the use of the StealC malware, as operators re-evaluate using it." With a relatively large, active user base now reliant on the platform, exposing a fundamental flaw in the management interface presents an opportunity to sow discord and uncertainty within the MaaS market segment. If operators cannot trust the security of the very panel used to manage their illicit activities, the perceived value proposition of the service rapidly degrades. This act serves as a form of proactive defense, weaponizing intelligence gathered from an infrastructure vulnerability to destabilize an active criminal enterprise.

Looking forward, this incident serves as a stark warning regarding the inherent trust models within criminal supply chains. As information stealers like StealC continue to evolve, integrating features like encrypted C2 communication and robust obfuscation techniques to resist endpoint detection, the focus of defensive operations must increasingly shift towards the administrative layers. The success of this XSS exploitation confirms that the centralized web panels, often designed with expediency over robust security in mind, are frequently the weakest link in the attacker’s chain.

The proliferation of MaaS offerings mandates that security vendors adopt proactive methods for monitoring and analyzing these backend systems, often accessible only through leaked source code or targeted penetration testing of known infrastructure. Future iterations of malware services will likely attempt to decentralize C2 management or implement client-side certificate verification for panel access to mitigate against this specific class of supply-chain attack. However, until such time, any platform that relies on a web interface for managing distributed malware instances remains susceptible to the same fundamental web application security flaws that plague legitimate enterprise software. The StealC case illustrates that in the high-stakes world of cybercrime, the tools used to manage the attack can become the greatest liability for the attackers themselves. The industry must prepare for a future where offensive infrastructure is routinely subjected to the same rigorous vulnerability analysis applied to enterprise targets.